After a 2011 nuclear disaster devastated Fukushima, Japan is still recovering.

At 4:17 a.m. on May 11, 2023, a loud siren jolted me awake. My always-on-silent phone was screaming, the screen reading: Earthquake Early Warning: Strong shaking is expected soon. Stay calm and seek shelter nearby.

The ground beneath my feet was shaking when I got out of bed. I was on the 14th floor of a hotel in Tokyo and scrambling to make sense of the situation. Dressed in my cute pajamas, I made a mad-dash to the door and realized that there were no scurrying footsteps in the sleepy hallways. What’s the protocol, I wondered, in or out? Flashing “Stay Calm” on an emergency alert doesn’t inspire rational thinking, surely not at that ungodly hour. But the moments of panic passed, and the hotel didn’t crumble like pieces of Jenga.

This geological event that incited my fight-or-flight response is not a rarity in the county. Japan is in the Pacific Ring of Fire, and its location is highly susceptible to seismic activity. Although it’s a battle against nature, the country has the world’s most sophisticated technology, with over 4,000 seismometers that give early warnings to residents. In use since 2007, it has become part of daily life. It wasn’t as accurate in 2011 when the Great East Japan Earthquake changed lives irreversibly.

Just two days before my own earthquake experience, I was in the Fukushima prefecture of Japan, the northeast part of the country that kisses the Pacific Ocean. A green blanket covered the town of Aizuwakamatsu, known for its rebuilt castle and the traditional Edo-period Ouchijuku village. Aizu was quieter and more laid back than Kyoto. My Japanese-style room at Aizu Higashiyama Harataki was stripped bare—no bed, no big furniture. Tatami mats, a table, two chairs, a wardrobe, and a mini-fridge with views of the mountains and a gushing waterfall. The private onsen room that I had picked also offered blissful views, much closer to the mountains in a zen-like al fresco setting. But there was a difference between the calmness of this town and the eerie desertion I witnessed two hours away.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

What Was Once the Future of Japan Is Now a Ghost Town

Angry clouds unfurled in the sky. The day was grey and gloomy, which seemed fitting for the sobering excursion to Futaba, a short distance from the seaside Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant. It was one of the main reasons my travel planner, I Love Japan, plotted Aizu on my 12-day Japan itinerary.

In May 2023, the town seemed like the set of a post-apocalyptic movie. It stayed sinisterly noiseless without the constant hum of traffic and human activity, a bad omen in a horrible nightmare. The once-busy streets replaced with debris, fallen trees, abandoned homes, barricaded roads, radiation meters in public spaces, and shuttered shops.

There were so many paddy fields that hadn’t been toiled in years. Plants and nature had taken over structures. Compared to the rest of Japan, there were hardly any businesses—restaurants, supermarkets, cafes, and shopping centers were noticeably absent in Futaba.

I barely saw a soul, maybe two cars passed us by. The newly-built Futaba station was unlike any other station in Japan—not one person, not one train that morning. But the radiation meter kept rising in the few minutes I took to take photographs in the rain. No one could have imagined that the nuclear power station that provided so many jobs—that was once advertised as the future of Japan—would turn this prefecture into colonies of ghost towns, silent and otherworldly.

Three Tragedies in One Day Rocked Japan

On March 11th, 2011, at 2:46 p.m., a 9-magnitude earthquake shook the eastern coast for six minutes. One of the world’s largest earthquakes triggered a tsunami with waves reaching 40 meters high. The cities and towns in the prefectures of Miyagi, Iwate, and Fukushima were leveled, and more than 20,000 were killed. But then a third tragedy happened: the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant had a meltdown.

After the earthquake, the nuclear reactors automatically shut down (as they were meant to), and generators kicked in. But the tsunami waves breached the sea wall, and the power failed. Three nuclear reactors overheated, and multiple explosions took place, damaging the buildings. Radiations leaked into the atmosphere and into the Pacific Ocean, and more than 160,000 people were evacuated across Fukushima, around the 12-mile radius. About 30,000 haven’t returned.

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum in Futaba narrates this story with real-life consequences, putting names and faces on obscure facts. Letters from children whose lives were uprooted, hazmat suits and radiation meters that were used, videos and interviews from locals and officials, footage of the earthquake, tsunami, and explosions, and the rebuilding efforts that have taken over a decade.

These tragedies were more than just statistics. People had to leave behind their pets in a flurry to evacuate. Several patients evacuated from hospitals died on the way. Thousands stayed in shelters for years, sometimes moved multiple times to other shelters. Cattle had to be euthanized. Wild boars took over the land. Agriculture disappeared overnight. Rice and vegetables were banned after high levels of radioactive caesium were detected. Later, rumors and scares destroyed the trust of the Japanese in Fukushima’s produce and seafood, crippling farmers and fisherpeople. Tourism to beachside towns dwindled.

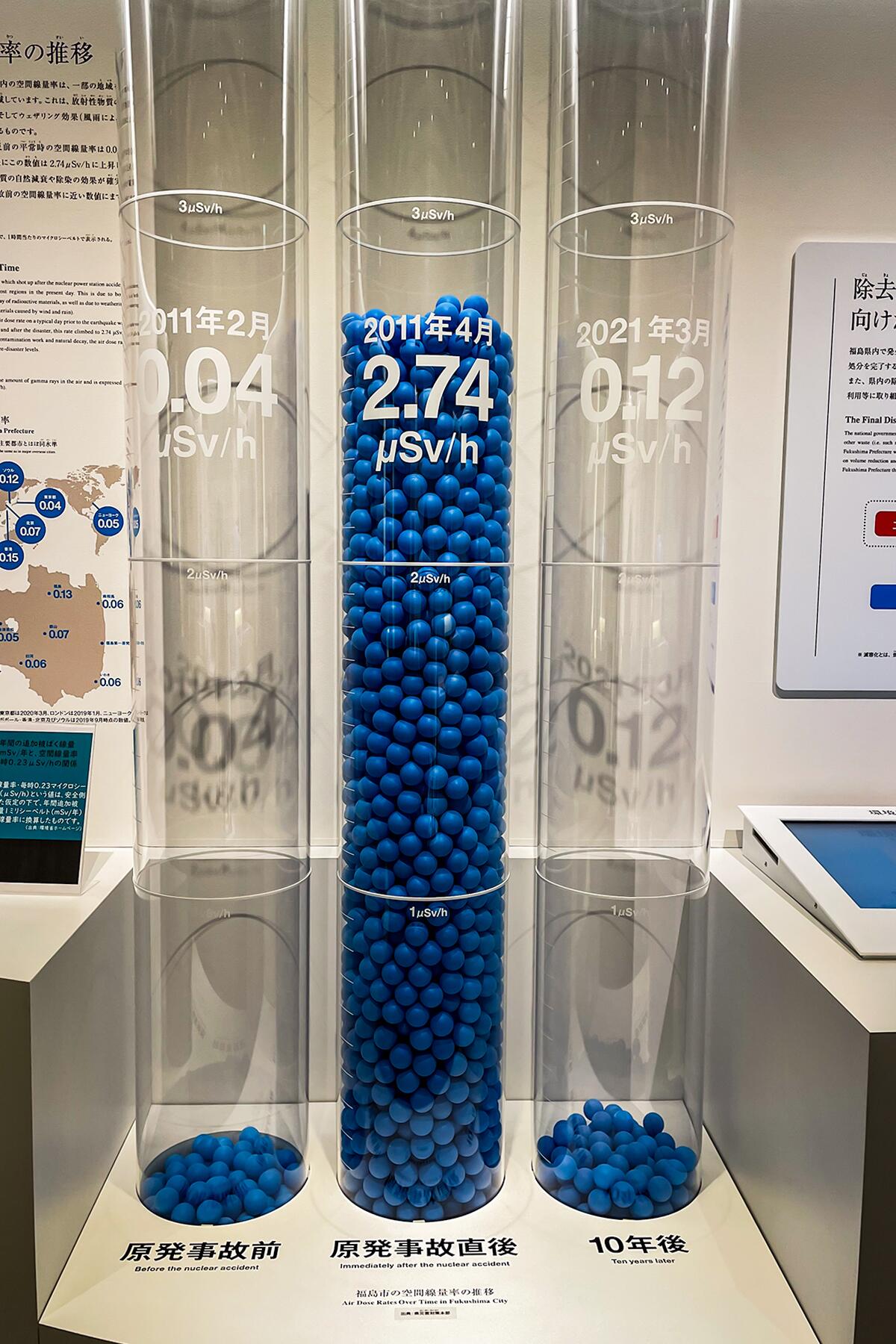

In the years that followed, the focus became decontamination of the region and decommission of the power plant. The efforts are still underway—topsoil is being removed, structures are being razed, and black plastic bags full of radioactive material can be easily spotted in fields. Many areas are still “difficult to return to,” and no one is allowed to enter as radiation levels remain high.

Is It Safe to Go Back?

People are coming back to safe-to-return areas; some visit on day trips to maintain their homes. Very slowly, it is resuscitating, but it’s a complex problem with no one-size-fits-all solutions.

In the town of Namie, north of the reactor, the evacuation order was lifted in about 20% of the town, while the other sections remain off-limits. Before 2011, the population of Futaba was 8,000. In February 2022, The Guardian reported that just three people had moved back after it was declared that the radiation levels had reached a safe level.

I met Kazuo Adachi at the museum, one of the many staff members who lived through the trifecta of disasters. He lives in the nearby town of Naraha, the first town in Fukushima to be declared safe for people to return. His family spent seven years in a shelter in Iwaki while he worked in Kyushu, Nagasaki. In Japanese, which was interpreted by my guide, he told us that Naraha now has a population of 4,000 people, but most of them are decommissioning workers employed by the nuclear plant. People don’t want to come back, he said. It has been 12 years, and they have restarted their lives elsewhere. Many, like him, are worried about their children. Before disasters struck, there were six elementary schools with hundreds of children. Now there is just one with 27 students.

Less than 3% of the prefecture is a no-entry zone. Much of Fukushima is safe. Aizu, for example, was protected from radiation due to the surrounding mountains and, thus, became an evacuation site. Decontamination efforts have helped in making the prefecture safe to live in some areas, while there may be others you can pass through in cars, staying just for a couple of hours.

Tourist numbers are improving, and countries (including the U.S., Taiwan, and the EU) have removed bans on Fukushima-produced foods. Last year, Iwasawa Beach in Naraha opened to the public.

These are painful memories for thousands of people, and my guide underscored again and again that no one wants to come to this side of the island for tourism—not yet, anyway.

But it’s an important piece of history, not just for Japan but for the world. It was a level 7 nuclear disaster on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, like Chernobyl in Ukraine. But in comparison, the Japanese nuclear meltdown released one-tenth of radioactive material, and the radiation level is being reduced with decontamination efforts. While Pripyat remains a no-go zone to this day, the Japanese government is deeply invested in rebuilding this prefecture. It is inviting corporations, constructing schools, hospitals, and homes, and lifting evacuation orders. The aim is to bring 2,000 people back to Futaba by 2030; other towns are also involved in revitalization.

There are 309 memorials, museums, and sites dedicated to the disasters in Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures as well as Sendai City. These Disaster Memorial Facilities are meant to teach lessons about the horrors of this disaster to both Japanese and foreign travelers.

Many, though, will learn the details of this tragedy another way, as it happened with Chernobyl. This year, Netflix has released a docu-series, The Days, that depicts the aftermaths of the deadly disaster and the chain of decisions in the succeeding days that led the country to this point.

An Unimagined Future

The nightmare is far from over. The nuclear plant needs to be decommissioned by 2051, which is a Herculean task undertaken by thousands of engineers, at astronomical costs (Japan has spent $82 billion already in clean-up). There are 880 tons of melted radioactive fuel and debris in three nuclear reactions that need to be removed and stored. Akira Ono, Chief Decommissioning Officer (CDO) at TEPCO, said in March this year that it’s difficult to know when or how the decommissioning will be completed. The company responsible for the plant has been sending robots to get images of the collapsed structure to understand what’s inside because humans can’t enter the highly radioactive containment zones. This has never been done before.

On top of that, the contaminated topsoil that was removed from the areas is right now sitting in plastic bags in storage units. It has nowhere to go, but as per Japanese law, it has to be out of the prefecture by 2045. Recycling plans involve using it for road construction (there’s enough to fill 11 baseball stadiums), but locals are not on board.

Another major point of contention, locally and internationally, is the decontaminated water. There are 1.3 million metric tons of treated water stored in 1,000 tanks at the site. The government has decided to gradually release this water into the Pacific Ocean, starting this year. The move lacks support from fishing communities who have still not recovered from the loss of business. This will be another blow to consumer confidence, no matter how safe the experts claim the water to be. China, South Korea, and some Pacific islands have raised concerns, too.

It’s difficult to move on from these tragedies when the relics are in your backyard. But Japan has built and rebuilt itself through terrible tragedies. If anything, it is resilient. I saw it in Nagasaki years ago. The Peace Statue serves as a reminder of the horrors of atomic energy that annihilated a city. But then you climb up Mount Inasa at twilight and look at the twinkling lights, representing its bright present and hope for the future.

Someday, we may be able to look at Fukushima like this. And along the way, there will be many lessons from its past.