“Alas! alas! small things come at the end of great things; a tooth triumphs over a mass. The Nile rat kills the crocodile, the swordfish kills the whale, the book will kill the edifice.”

On April 15, 2019, the world watched in shock as the roof of Notre Dame—that enduring symbol of Parisian beauty and grace—burned.

By the time the flames had been extinguished, the 850-year-old cathedral was still standing but the damage to Notre Dame’s roof was extensive, the spire having completely collapsed. The cause is believed to have been an electrical short that sparked in the attic where the fire had originated. Within a week of the fire, people and organizations from all over the world had pledged over a billion dollars toward Notre Dame’s restoration.

Considering how universally beloved Notre Dame is today, it’s difficult to imagine that there was a time when the cathedral’s survival was of little concern to the general populace.

After the French Revolution, the cathedral was seen not as a testament to Parisian grace and beauty, but a testament to the clergy’s rule as the First Estate under the Ancien Régime. After the Revolution, the Cult of Reason and the subsequent and more deistic Cult of the Supreme Being were established as replacements for Catholicism. Notre Dame, now public property, was rededicated to the Cult of Reason and the cathedral’s relics and treasures—including its bells—were destroyed or stolen.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Though Napoleon eventually banned both cults and made Notre Dame, once again, property of the Catholic Church, the cathedral would remain in a state of disrepair for years.

By the 1820s, Notre Dame’s grandeur had been all but vanquished and there was serious consideration that the cathedral should be demolished altogether. The fact that this was a possibility inspired writer Victor Hugo to lay out the case for Notre Dame’s survival in a paper entitled “War to the Demolishers.” It didn’t have the impact he’d hoped for. And while you may not have heard of that particular work, you’ve probably heard of his second attempt at campaigning for the preservation of the cathedral. Notre-Dame de Paris or, as it’s known to Anglophones, The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Published in 1831, the sweeping epic of a novel was a bonafide blockbuster. The dramatic story successfully served as a compelling conveyance of Hugo’s messaging that “architecture is the great book of humanity” and Notre Dame’s status as one of that book’s most important pages.

“Thus, during the first six thousand years of the world, from the most immemorial pagoda of Hindustan, to the cathedral of Cologne, architecture was the great handwriting of the human race. And this is so true, that not only every religious symbol, but every human thought, has its page and its monument in that immense book.”

Alfonso de Tomas/Shutterstock;

Bill Perry/Shutterstock

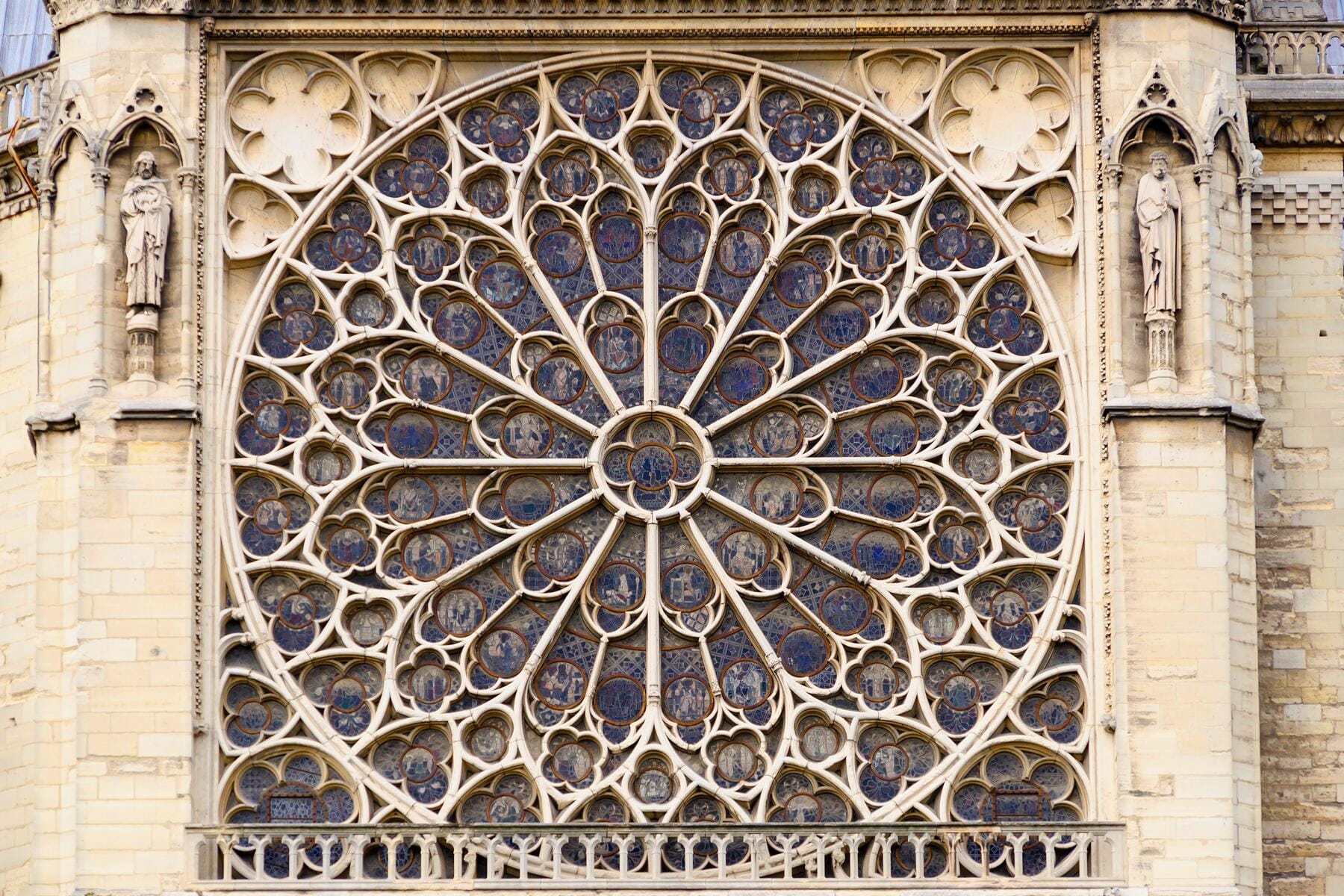

Hugo regarded the Gothic architecture that Notre Dame cathedral so spectacularly embodies as the last true expression of architecture as a medium. The architecture of Hugo’s age was concerned with taking styles and ornamentations from earlier, bygone styles.

Hugo argues that in spite of their religious functions, the buildings themselves are the artistic expression of the architects and for the edification of all that look upon them. “The architectural book belongs no longer to the priest, to religion, to Rome,” writes Hugo. “It is the property of poetry, of imagination, of the people.” He cites the Gothic style as evoking, before all else, “the citizen.”

Perhaps this is why, despite seeing it in countless postcards and film adaptations of Hugo’s novel, Notre Dame can still inspire such awe in its visitors. That, though we may be more familiar with Quasimodo and Esmerelda than the particulars of architecture as an essential form of poetic expression, Notre Dame’s Gothic style does inherently speak first and foremost to the citizen.

The result of Hugo’s work is, of course, history. The book, and by extension, Hugo’s message were so popular that it led to the restoration efforts that culminated in the cathedral that we’ve known for much of the modern era. In the wake of the April 15 fire, there was a brief moment where it was considered that the new roof would be completely different and modern (a rooftop pool would certainly have Hugo spinning in his Panthéon crypt.). But it was ultimately decided that the cathedral would be restored to “its last known visual state.” When the restoration is completed (estimated for 2024), it will be just the latest chapter in the book of Notre Dame.