A village frozen in time memorializes a tragic history.

“Souviens-toi,” proclaim the thin red letters as I enter the village. “Remember.” Another sign simply whispers, “Silence.”

At face value, it would appear that I’m entering any of France’s thousands of historic little villages, with their winding lanes, mature chestnut trees, and stone houses behind flower-draped fences.

I am, but I’m not.

The little village of Oradour-sur-Glane didn’t feel much of the effects of World War II, tucked deep as it was in Vichy France in the Limousin countryside outside of Limoges, far away from the fighting. Food was plentiful here—as was tobacco. Men worked the farms, women took care of their homes, children went to school.

And then came June 10, 1944.

On that day, a market day Saturday, soldiers of the 2nd Waffen-SS Panzer Division surrounded the village and rounded up its inhabitants (and anyone else who had the bad luck to be in town that day), hauling them out of their homes and violently pushing them to the village square for an “identity check.” The men were then separated from the women and children, with the men being taken to several barns on the town’s outskirts and the women and children forced into the village church.

The victims waited, wondering their fate, and then, when the word came, the SS soldiers mowed down the men with machine guns and lit a smoke bomb in the church, asphyxiating the women and children; anyone who didn’t die quick enough was shot. In the end, 642 total were murdered, 62 of them under six years of age. The Nazis built pyres over the bodies, looted the empty homes, and systematically set the houses on fire.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Why did this happen?

You can say it was in revenge for Resistance activities in the region, or vexation that the Normandy landing had occurred. But there’s really only one reason this happened, and that’s plain old-fashioned hate. It’s the quest to feel superior, to dominate, persecuting and discriminating those perceived as weak, or of lesser value in a most unholy frame of mind.

And for that reason, General Charles de Gaulle declared the village in 1945 a permanent national monument and mandated that it remain exactly the same as it was on that horrific day so that the world wouldn’t forget what happens when hatred is unleashed and allowed to run unchecked.

Today, you can visit the frozen-in-time Martyr’s Village, which is entered via an underground passageway from the Center of Remembrance. Here’s what I discovered on a recent visit.

The Center of Remembrance of Oradour

The visit starts at the multi-room permanent exhibition of photographs, films, maps, and diagrams that grapple with Oradour’s history from the broad perspective of the rise of Nazism in Germany to the specific horrors of that day.

Every last detail contributes to the sacredness of the space, such as the fact that all discussion pertaining to Nazis is written in black and red type; and a gap was left between the boards of explanation and the walls so the hatred doesn’t touch Oradour again.

I read how Oradour was considered a safe place, explaining the number of refugees residing here, including many escaping Spain’s civil war as well as others fleeing the fighting in the northern and eastern parts of France.

One of the event’s many tragedies was the fact that some of the murderers were young Frenchmen from Alsace. When Germany annexed Alsace in 1940, these “Malgré-nous,” as they were called (“against our will”), became Waffen SS against their will. So when their detachment attacked Oradour, these Alsatian soldiers were in fact assaulting some of their neighbors and friends. At a postwar military tribunal they were convicted to life in prison and one to death, only to be pardoned in the name of national reconciliation—a betrayal to the memories of the Oradourian dead and one that did little to help the region find closure.

One panel catches my eye, stating that, while what the Nazis did in Oradour was unusual in France, it was done a thousand times on the Eastern Front. I close my eyes, trying to avoid the picture of widespread horror, the pervasive hatred.

The last room is a reflection space with reflecting mirrors and civil rights quotes illuminated on the floor, and I catch my breath, seeking solace in the words of the ages.

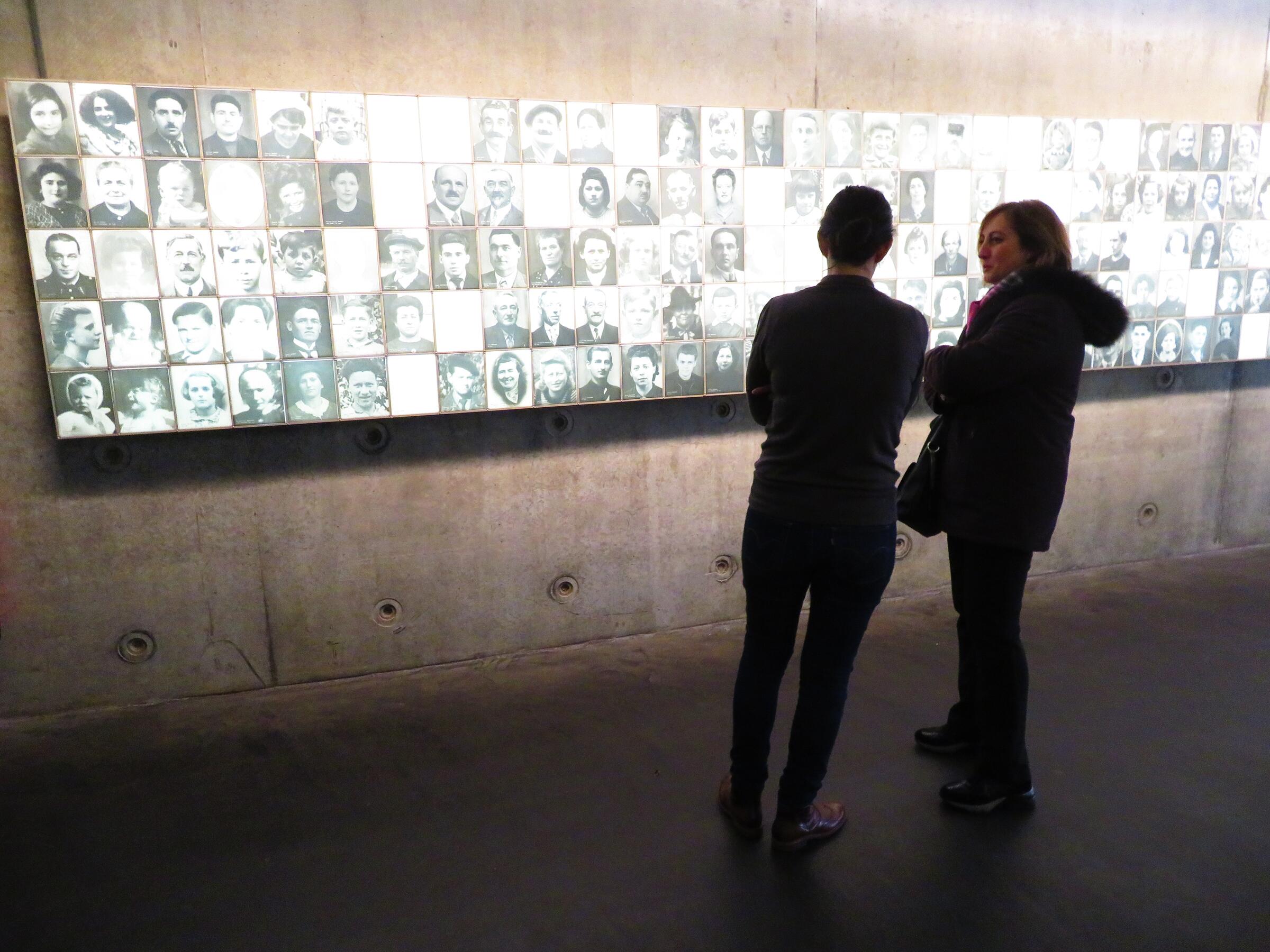

And then, exiting the center into the empty village, I walk past walls of black-and-white photographs depicting those murdered on that day. Their innocent eyes stare out at me, grandmothers and grandfathers, little children, couples smiling on their wedding days. Lest we forget, these were real people, not just a calamity against a town.

The Martyr’s Village

The village itself is small, just three or four streets on a grid. My mind wanders as I stroll the sunny lanes against a backdrop of chirping birds and clumps of colorful wildflowers.

The trees growing there, lush and alive, were there on that day, serving witness to the cries and screams of the victims, the sounds of gunfire, and then silence.

The ancient church, its nave so small, is quiet, peaceful, and I push away the appalling mental images of 400 frightened, pleading women and wailing children succumbing to their fate.

The stone buildings, at least what’s left of them, are charred and crumbling, the roofs lacking altogether, their emptiness bespeaking another time when lives were lived in their folds.

Some buildings are marked with signs speaking of people once going about their daily businesses: Mme. Reignier, Dentiste; F. Brouillaud, Café/Coiffeur; P. Poutaraud, Garage.

Cars of ’40s vintage remain parked on the streets, oxidized and breaking down over the years, forever waiting for their owners who never returned.

Rusty bikes lean in eternity against walls, complete with chains and pedals.

But perhaps the eeriest sights are the Singer sewing machines resting inside the grassy foundations of scorched walls. Cast iron survives the test of time, though mortal flesh does not.

Just outside the village awaits the memorial cemetery, overshadowed by a towering stele inscribed with the victims’ names. Memorial tablets remember different families, and two glass-roofed ossuaries contain ashes and bones, and my mind wrestles again with the shocking thought that these were real people, suffering a hatred-filled fate.

As I drive away into the peaceful Limousin countryside, the one lingering thought I have, the underlying message of the site: We can be petrified and terrified, and do nothing about injustice. Or we can be sure to do our part and ensure nothing like this happens again. Voices whisper from the past: Ask questions, just don’t obey.

Addendum

Just this past August 2020, the sign at the entrance to the memory center was defiled, with the word “martyr” being replaced with “liar.” Philippe Lacroix, the mayor of Oradour-sur-Glane (the twin village built after the war), said: “We know what happened here but obviously there are always people who try to tell lies.” And Prime Minister Jean Castex stated: “To soil this place…is also to soil the memory of our martyrs.”

It serves as a poignant reminder, given the state of the world these days, that we must never forget that hatred exists and we must rally and fight it.