Charles Bridge

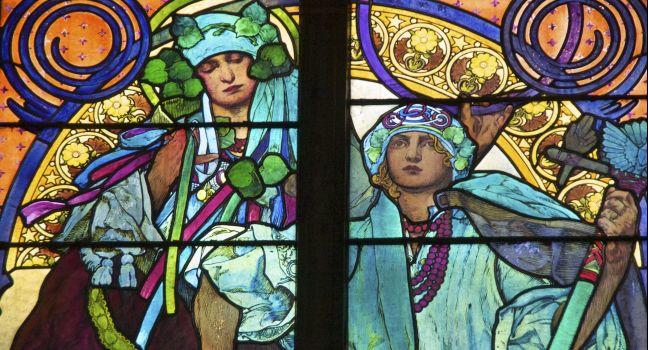

This is Prague's signature monument, and quite rightly so. The view from the foot of the bridge on the Staré Mĕsto side, encompassing the towers and domes of Malá Strana and the soaring spires of St. Vitus Cathedral, is nothing short of breathtaking. This heavenly vista subtly changes in perspective as you walk across the bridge, attended by a host of baroque saints that decorate the bridge's peaceful Gothic stones. At night its drama is spellbinding: St. Vitus Cathedral lit in a ghostly green, Prague Castle in monumental yellow, and the Church of St. Nicholas in a voluptuous pink, all viewed through the menacing silhouettes of the bowed statues and the Gothic towers. Night is the best time to visit the bridge, which is choked with visitors, vendors, and beggars by day. The later the hour, the thinner the crowds—though the bridge is never truly empty, even at daybreak. Tourists with flash cameras are there all hours of the night, and as dawn is breaking, revelers from the dance clubs at the east end of the bridge weave their way homeward, singing loudly and debating where to go for breakfast. When the Přemyslid princes set up residence in Prague during the 10th century, there was a ford across the Vltava here—a vital link along one of Europe's major trading routes. After several wooden bridges and the first stone bridge washed away in floods, Charles IV appointed the 27-year-old German Peter Parler, the architect of St. Vitus Cathedral, to build a new structure in 1357. It became one of the wonders of the world in the Middle Ages. After 1620, following the disastrous defeat of Czech Protestants by Catholic Habsburgs at the Battle of White Mountain, the bridge became a symbol of the Counter-Reformation's vigorous re-Catholicization efforts. The many baroque statues that appeared in the late 17th century, commissioned by Catholics, came to symbolize the totality of the Austrian (hence Catholic) triumph. The Czech writer Milan Kundera sees the statues from this perspective: "The thousands of saints looking out from all sides, threatening you, following you, hypnotizing you, are the raging hordes of occupiers who invaded Bohemia 350 years ago to tear the people's faith and language from their hearts." The religious conflict is less obvious nowadays, leaving behind an artistic tension between baroque and Gothic that gives the bridge its allure. Staroměstská mostecká věž (Old Town Bridge Tower), at the bridge entrance on the Staré Mĕsto side, is where Peter Parler, the architect of the Charles Bridge, began his bridge building. The carved façades he designed for the sides of the tower were destroyed by Swedish soldiers in 1648, at the end of the Thirty Years' War. The sculptures facing Staré Mĕsto, however, are still intact (although some are recent copies). They depict an old and gout-ridden Charles IV with his son, who became Wenceslas IV. Above them are two of Bohemia's patron saints, Adalbert of Prague and Sigismund. The top of the tower offers a spectacular view of the city for 100 Kč; it's open daily year-round from 10 am to between 6 and 10 pm. Take a closer look at some of the statues while walking toward Malá Strana. The third one on the right, a bronze crucifix from the mid-17th century, is the oldest of all. It's mounted on the location of a wooden cross destroyed in a battle with the Swedes (the golden Hebrew inscription was reputedly financed by a Jew accused of defiling the cross). The fifth on the left, which shows St. Francis Xavier carrying four pagan princes (an Indian, Moor, Chinese, and Tartar) ready for conversion, represents an outstanding piece of baroque sculpture. Eighth on the right is the statue of St. John of Nepomuk, who according to legend was wrapped in chains and thrown to his death from this bridge. Touching the statue is supposed to bring good luck or, according to some versions of the story, a return visit to Prague. On the left-hand side, sticking out from the bridge between the 9th and 10th statues (the latter has a wonderfully expressive vanquished Satan), stands a Roland (Bruncvík) statue. This knightly figure, bearing the coat of arms of Staré Mĕsto, was once a reminder that this part of the bridge belonged to Staré Mĕsto before Prague became a unified city in 1784. For many art historians the most valuable statue is the 12th on the left, near the Malá Strana end. Mathias Braun's statue of St. Luitgarde depicts the blind saint kissing Christ's wounds. The most compelling grouping, however, is the second from the end on the left, a work of Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff (son of Johann) from 1714. Here the saints are incidental; the main attraction is the Turk, his face expressing extreme boredom at guarding the Christians imprisoned in the cage at his side. When the statue was erected, just 31 years after the second Turkish siege of Vienna, it scandalized the Prague public, who smeared it with mud. During communist rule, Prague suffered from bad air pollution, which damaged some of the baroque statues. In more recent years, the increasing number of visitors on the bridge has added a new threat. To preserve the value of the statues, most of the originals were removed from the bridge and replaced with detailed copies. Several of the originals can be viewed in the Lapidárium museum. A few more can be found within the casements at the Vyšehrad citadel.