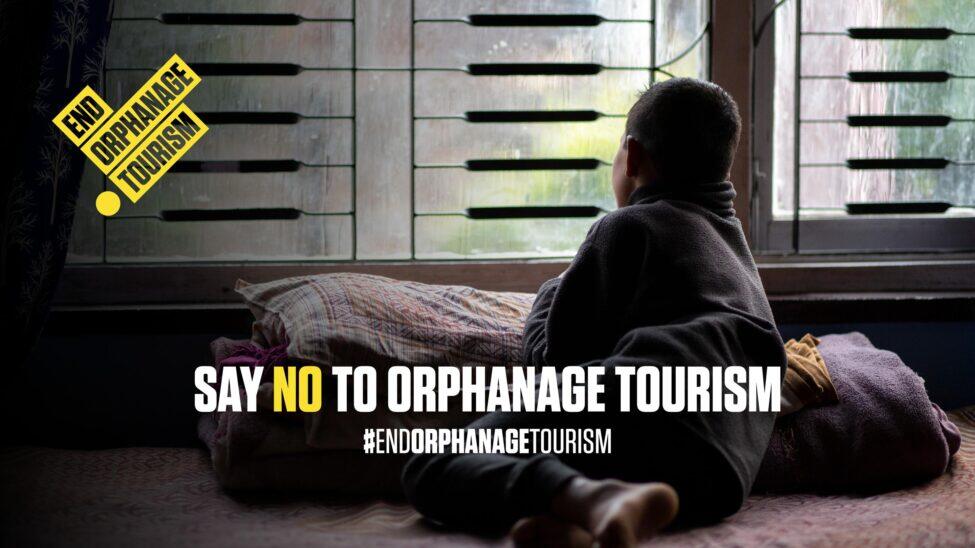

The #endorphanagetourism campaign targeting tourists traveling from the U.K. comes as U.S. organizations also warn them about the dangers that children’s institutions pose to young ones, backed up by decades of research.

Content warning: This article discuses child abuse.

For nearly 10 years in the 1980s, from the age of four until she was a teenager, Rukhiya Budden called an orphanage in Nairobi, Kenya, home. Her mother was alive but had mental health issues and was unable to support her, so Budden stayed in the privately funded home. Every week, strangers, including well-meaning travelers from all over the world would come and go, a practice known as “orphanage tourism.” Since then, there have been decades of scientific research backing up the long-lasting physical and emotional impact of orphanage tourism on children.

“It was horrible,” says Budden. “Although the visitors leave feeling good about themselves, the children are left with another feeling—abandonment and their hope to be reunited with their families shattered.” She later developed anorexia as a result of the mental anguish of growing up in an institution, where she witnessed other children being abused. Today, motivated by her experience, she’s a child psychotherapist and ambassador for global charity Hope and Homes for Children (HHC), an organization trying to abolish orphanages.

In the lead-up to Christmas, HHC, the U.K. Border Force’s National Safeguarding – Modern Slavery team, and The Association of British Travel Agents (ABTA) are urging tourists not to visit orphanages. Despite 80% of children in similar situations to Budden’s–those who are believed to be orphans with living family members—5.4 million of them continue to languish unnecessarily in these homes around the world today, says HHC. Half of the children confined in orphanages suffer abuse and sexual violence.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

The #endorphanagetourismcampaign, which launched earlier this year at the six busiest U.K. airports including Heathrow and Gatwick, plus Eurostar terminals, involves officers warning passengers traveling to popular “orphanage tourism” hotspots like Cambodia, Thailand, Nepal, India, Uganda, Kenya, and Sierra Leone. According to analysis by the research firm Censuswide, 57% of Brits have or would like to donate money to institutions or go to one. But alarmingly, three quarters don’t know that these “orphans” have families, the data also found. The organizations involved in the campaign say that already they’re changing popular perceptions of orphanages among holidaymakers.

In October, an independent expert appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) to follow and report on the sale and exploitation of children released a report on the risks of this practice from volunteers, or what’s now known as “voluntourism.” It’s described as one of tourism’s fastest-growing markets and said to be worth $3 billion U.S.D. annually, the U.N. special rapporteur highlighted “orphanage tourism” in her research.

The Inter-Parliamentary Union, the worldwide organization of national parliaments, adopted a resolution on the role of Parliaments in reducing orphanage trafficking in October. It says that it “condemns all forms of orphanage trafficking and orphanage tourism, including orphanage volunteering.”

Countries where most “voluntourists” are originating from include the U.K., Australia, and others in Europe, plus Singapore and South Korea, says Rebecca Nhep. She’s a Cambodia-based senior technical advisor with the Better Care Network (BCN), part of a network of agencies facilitating an international exchange of information on the subject of children without proper family care. The U.S. is another big market, with the Christian community in particular, says Nhep. Many are on what’s known as “mission trips.” This is where Christian groups travel abroad, particularly to countries in Africa, Latin America or South America, in an attempt to serve and spread the Gospel, with a particular focus on orphaned or vulnerable children. These happen year-round but are especially common over school breaks and around the holidays. A 2021 survey by the Christian research organization Barna Group found that the majority of U.S. Christians are ill-informed on the subject, believing in the necessity of orphanages, and unaware of the history of abuse.

Elli Oswald, the executive director of Faith to Action, a U.S.-based nonprofit that guides Christian groups, churches, and people wanting to help orphaned and vulnerable children, recently conducted training with “a large mission trip-sending agency.” She says that “several shared their plans to visit an orphanage during upcoming trips.” But Faith to Action now outright warns organizations about going to visit children “to cuddle for a few days, then leave [them] behind,” and instead encourages family-based care and activities.

In December 2018, Australia passed the Modern Slavery Act, which includes orphanage trafficking in its definition of slavery, becoming the first country in the world to do so. Several other countries have made progress on orphanage tourism since. Canada has since followed Australia, with a law that comes into force on January 1, 2024, and New Zealand is likely to take action in 2024 as well. Meanwhile, the Netherlands has proposed a compulsory criminal background check for all overseas volunteers working with children, but is now strongly advising against helping out in orphanages. Ireland has created a working group with the government to end orphanage volunteering. Fiji has set up a code of conduct for tourism service providers, with minimum standards of terms of behavior and conduct to guide them.

The mainstream tourism sector in the countries that are sending the bulk of volunteers to orphanages has mostly come on board following Australia’s leadership, says Nhep.

Liz Manning, the manager of global supply chain at Intrepid Travel, a responsible adventure tourism group, says Intrepid evaluated their own reporting on modern slavery throughout their range of tourism products, and their suppliers are now asked if they work with organizations that engage in providing residential care to children. They also evaluate if suppliers contract or engage with any social enterprises, charities, or other organizations involved with offering residential care to children.

Other tourism operators that have acted on the issue include Responsible Travel, as well as Africa Impact, Pepy Tours, Projects Abroad, Tourism Cares, and World Challenge, according to Rethink Orphanages, an international coalition that aims to prevent families from being separated and children from being placed into institutions unnecessarily.

But the “voluntourism” sector, which is highly unregulated compared to the mainstream travel industry, is still proving to be a barrier, says Nhep. There are still many “in-country pathways” that exist for tourists to visit orphanages. “People from the U.S., U.K., Australia, or Europe might jump on a plane without the intention of going to visit an orphanage,” she says. “When they arrive in [a] country, there’s all of these opportunities put in front of them, whether it’s at hotels, [through] their transport provider, their local tour guide that on a site says, ‘Hey, do you want to visit an orphanage?’”

Education is key, says Nhep.

To bring about sustainable change for orphans, travelers are better off donating to organizations that reunite children with families, organizing fundraising events for them, or calling out “orphanage tourism” on social media, says HHC. Instead of mission trips, Faith to Action now recommends advocacy trips to learn about the root causes of family separation, to address this. Buying locally from shops and markets is another way to support orphans without inflicting harm on them, an ABTA spokesperson adds.

Rwanda is one country that hopes to become orphanage-free in the next two years. The orphanage where Budden lived is still open in Kenya today. Only two days ago, she heard that a friend who she’d been in the orphanage with had died. Budden is now determined to educate as many people as possible that children need to be in families, and not institutions. She says, “I’m very lucky that I’m able to make this difference, and I always say if I can reach just one person, that’s all that matters to me.”