Paris' open-air bookshop is trying to refresh its image.

It’s a Sunday, and the sidewalks along the Seine are full of people, particularly on this stretch of road opposite the helter-skelter of cranes and scaffolding encasing the Nôtre-Dame cathedral.

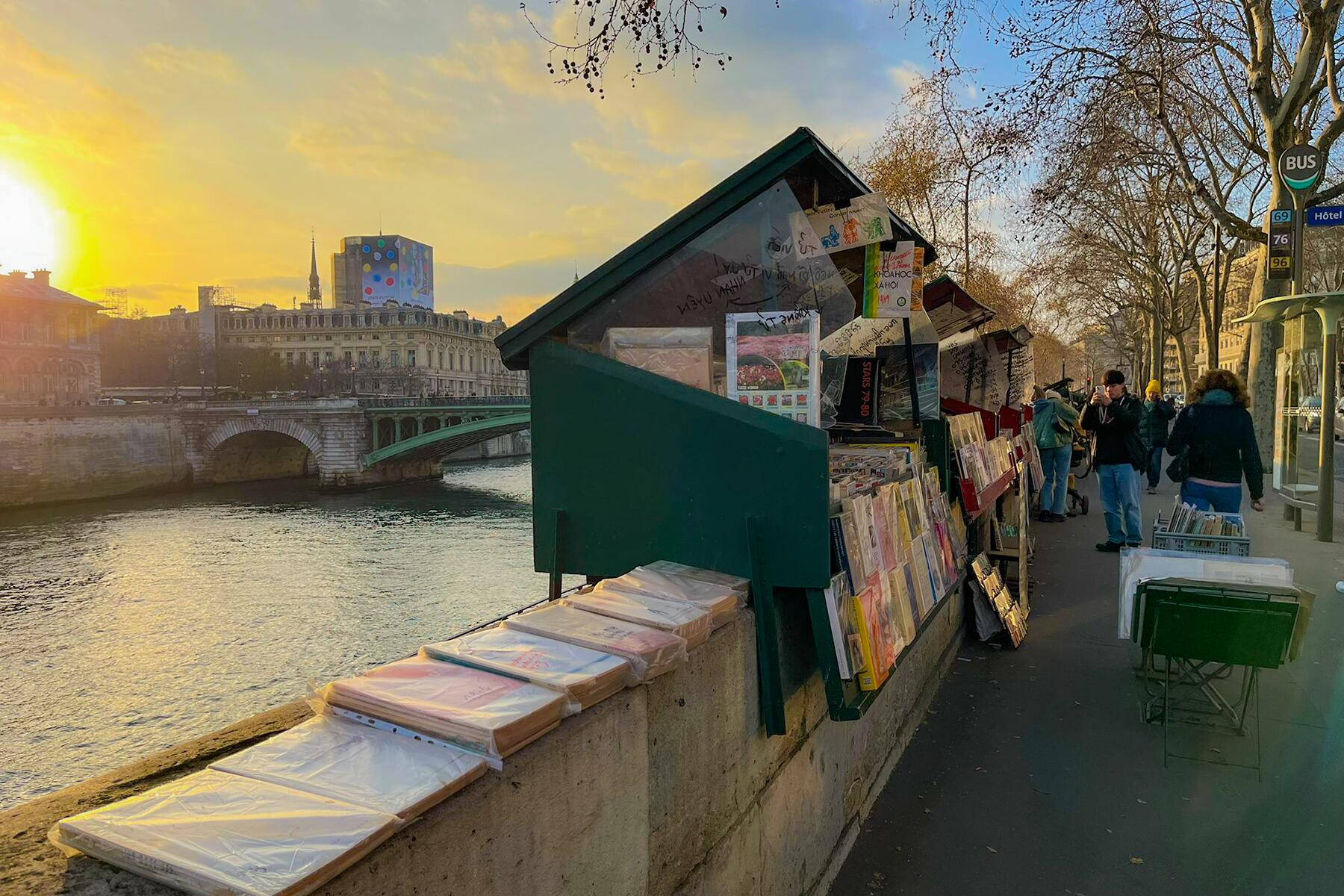

Françoise Louvet is taking advantage of the sunny February afternoon and has opened her stall of books and other wares, hoping to make a few sales. Louvet is one of around 230 bouquinistes, the Paris booksellers who work out of the iconic dark-green boxes, or “boîtes,” that line the quays in the French capital.

“I’ve been a fixture on the quays since I was 18. Normally this job doesn’t get passed on to your children, but my mother was a bouquiniste, and when she stopped working, I took over her boxes,” Louvet explains.

She’s sitting in a foldable camping chair, facing her bookstall with boxes opened like clams, spilling out old French newspapers, books, postcards, and engravings.

Paris’ Bookstalls Are a Centuries-old Tradition

Louvet is part of a tradition that dates back 450 years. The signature dark green of the wooden boxes perched on the stone walls lining the Seine is the same green used for the city’s metro entrances, public fountains, and park benches. The stalls follow the river’s course like a dashed line, from the Louvre to Pont Marie on the Right Bank and from the Musée d’Orsay to the Institut du Monde Arabe on the Left Bank.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Now 71 years old, Louvet says she doesn’t open her bookstall as often as she used to. But, if the weather’s good, she can work long days. I ask her if she ever gets bored waiting for a tourist to buy some postcards for a few euros. She looks almost scandalized by the suggestion.

“I never get bored!” she declares. “It’s a constant cinema! You have the whole world walking by.”

It’s not easy work, either. Bouquinistes are out despite the weather, rain or shine.

“If we’ve opened and it starts to rain, we protect the books with a plastic cover and carry on. We breathe in pollution all day. I’ve worked when it’s freezing; I’ve put gravel on the ice in front of my shop, so people don’t slip over,” Louvet says. But the job is threatened by stronger headwinds than the meteorological kind.

The COVID-19 pandemic, the Yellow Vest protests, and the pervasiveness of online shopping have all negatively impacted the trade.

“For a long time, there were no tourists. And with the cost-of-living crisis, the strikes, and the debate over the retirement age, people are very careful with what they spend,” says Jean-Marc Millière, a bouquiniste who has a stall on the other side of the river. “You can’t eat a book! Even spending five euros–that’s the equivalent of four baguettes.”

But it’s the internet that has by far been the most damaging change to the profession. “New generations have grown up with the habit of doing everything online. They read online; they buy online. Sometimes we have customers tell us, ‘It’s cheaper on the internet’–well, buy it on the internet, then!” says Millière ruefully. He’s been a bouquiniste for two decades after learning the trade by working as an ouvre-boîtes (a play on words that means an assistant who helps bouquinistes open the boxes and is also the French word for can-opener).

Eking Out a Living Selling Books on Paris’ River Banks

“Today, I haven’t sold anything. Zero,” Millière says, shrugging. “But it’s fine. I chose this life because it gives me freedom. I prefer to be independent.”

Although secondhand books are the heart of the job, many bouquinistes have added tourist trinkets like postcards, coasters, and fridge magnets to their stalls to scrape a living. Some refuse to, however, like Jean-Marc Millière’s neighbor François.

“My customers have always been individuals, collectors. But there are fewer and fewer of them,” he explains.

Sitting on the bench just across from his stall, where he sells mostly vintage French pornographic magazines and erotica, he describes how some days he doesn’t sell a single item. He earns about 600 euros a month, barely enough to live on. It’s the same with many of the bouquinistes. Françoise Louvet says that she takes in about 300 euros a month and can only get by because of her state pension.

With Paris hosting the Olympics in 2024, many booksellers hope that business will pick up with the influx of visitors to the city.

“After all, it’s not the first crisis that us bouqinistes have lived through,” adds Millière with a wink. “We survived the wars, the German occupation, even the French Revolution!”

Some bouquinistes have started offering card payments, and others catalog their books in online portal that allows people to reserve a book in advance and then pick it up in person. Louvet doesn’t want to use technology in her business, however.

“We talk so much nowadays about being environmentally friendly, recycling, and buying secondhand. Well, this is what we do! We sell old books. Our job is essentially recycling!” she laughs.

Bringing the Trade to the 21st Century

Jérôme Callais, the president of the association of bouquinistes, has gone a step further: He wants the bouquinistes to be added to UNESCO’s Intangible Heritage list, which he thinks will have the effect of giving the profession the respect and attention it deserves. The French government has supported the bid and in 2019, added the booksellers to France’s list of cultural and immaterial heritage.

On a more practical level, many bouquinistes have been in the job for decades, and Paris City Hall wants to rejuvenate the trade’s image. City authorities have started opening public applications to be a bouquiniste, and recent rounds of applications–the latest ended in January–have brought younger booksellers to the city’s sidewalks.

Paname Bouquine!

Among them are Camille Goudreau and Elena Carrera, two women in their thirties, whose stalls are situated just in front of the ornate and imposing city hall building. They created the first bouquinistes festival, called “Paname Bouquine,” meaning “Paris reads.”

“Of course, the tourists love us, but we’ve forgotten the French. They’ve basically stopped buying from us. We’re trying to restore our image!” explains Louvet, who participates in the festival.

For two days in the summer, the river banks come alive with book signings, open-air readings, book clubs, games, and treasure hunts–a bid to encourage people to speak to the booksellers and perhaps realize that there are other ways to buy books than online. This year, the festival falls on the first weekend of July.

Although times are tough, the bouquinistes have been a fixture of the Paris landscape for hundreds of years, and Louvet doesn’t think there’s any risk of the trade dying out. Gesturing towards the bookstalls nearby with Nôtre-Dame rising in the distance, she smiles and says, “How could this stop? We’re part of the soul of Paris.”

If these stalls can't survive, Paris will lose a substantial slice of its soul.