In Agra, marble inlay, a technique where white marble is carved in an intricate design to make space for an inlay of patterns crafted from precious and semi-precious gemstones, is a steadfast—and now, famous—tradition.

In India, there is a palpable feeling of everything and everyone being altogether at once. For a first-time visitor, the Delhi Airport is an appropriate introduction: in October, the humidity still boils; the passengers, weaving in and out of crowds, begin to sweat; and there is even a band, clad in colorful knee-length kurtas, wired in a lively beat that makes you wonder about what lies beyond.

It doesn’t take long for any visitor to be thrust into the pulse of life in Delhi. Small businesses are the most omnipresent part of daily life in India’s big cities: Luscious carpets, glistening saris, bejeweled bowls, leather goods, and sheets after sheets of pashmina scarves line the storefronts of almost every street you walk. Street stalls that sell steamy pani puri—crispy dough shells encasing spiced mashed potatoes and lentils or liquids—or a cartful of fruits are parked almost everywhere that they are able, emanating pungent aromas of oiled cumin and sweet limes. Add to this the sounds of Indian roads: bikes, manual and motorized rickshaws, and cars merging and moving as one continuous stream, honking and blaring their horns to signal their approach. It is in this pandemonium of sounds, smells, tastes, and visual enchantments that you must find your way to treasure.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

S

ome four hours’ drive away from Delhi lies the city of Agra, where treasure is abundant. The technique of marble inlay—during which white marble is carved in an intricate design to make space for an inlay of patterns crafted from precious and semi-precious gemstones—is famous here, and that is reflected in the predominance of marbles in the shops’ wares. Precious stones like emeralds, rubies, and sapphires, as well as semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli, turquoise, and malachite are all used to create refined, decorative imagery within marble. The end result is captivating, heirloom-quality objects—whether it be a tray, a vase, or a tabletop—that sparkle in a multicolor splendor.

But the small objects are merely derivations of the grandest treasure of all. The Taj Mahal, situated on the bank of the Yamuna River that threads through Agra, remains as the superlative example of the craft. The way that the gleaming white mausoleum emerges beyond the main gateway—an architectural feat in its own right—is bewitching. The decorative scheme is identifiably Islamic, with an emphasis on floral, geometric, and calligraphic patterns: passages from the Quran are inlayed in black marble or jasper, in the expansive and delicate curvature of the Thuluth script; a wide assortment of flowers and floral tendrils are carved—some in bas-relief and others with colorful stone inlay—into every imaginable corner and surface. The overall effect is a diffused, almost otherworldly, luminosity.

India under the Mughal rule was brimming with wealth; there were no shortages of raw materials, and the royals were capable of rewarding a hefty sum for the best artisans’ work. “Precious and semi-precious stones were sold in flea markets like vegetables,” Akilesh, my local guide provided by Trafalgar Tours, told me. “The best artisans from across the globe wanted to come work in India.”

And come to work they did. Some 20,000 builders and artisans from across the globe were brought to Agra in the 17th century to erect the Taj Mahal, including Italians practicing the technique of pietra dura—the process of using fitted stones to create decorative images. On the Indian subcontinent, the technique is referred to as parchin kari; the origin of the technique is sometimes debated, but most agree that the Italian artisans’ pietra dura served, at least, as an inspiration.

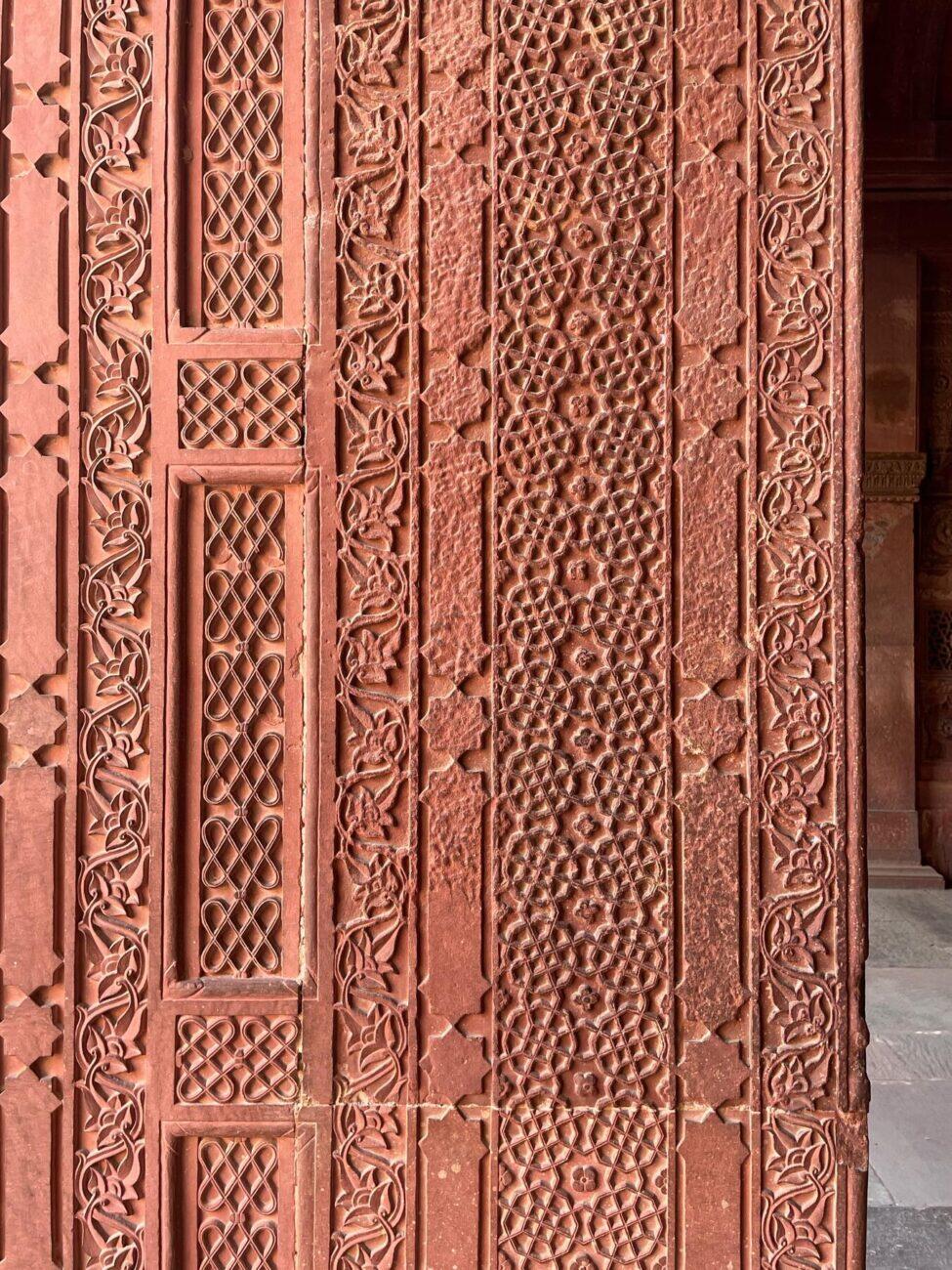

The sculptural complexity of the marble inlay process is perhaps best observed in Agra Fort, where the absence of the fitted stones exposes the inlay craftmanship in high relief. The fort served as the main residence of the Mughal royals until the capital was moved from Agra to Delhi, and was thus endowed the architectural opulence of a royal palace. The carvings that adorn the red sandstone—which served as a base layer for the marble and the stone inlays—are as intricate and masterfully rendered as the sculpted cornices of some of the finest European basilicas.

So where are the marbles and the stones? The skeletal remains of Agra Fort are a sign of India’s colonial occupation that began in the mid-19th century: the imperial British filled ships after ships with the precious materials that they dug from these walls and transported them back home. The frescoes that once lined the ceilings were chipped away for their gold content and destroyed. Still, it’s a thrilling, albeit wistful, mental exercise to imagine the fort’s original form: white marble walls gleaming with multicolored stones, fine curtains and draperies swaying in the breeze, and the floors lined with sumptuous silk carpets.

K

alakriti, a boutique in Agra that specializes in marble inlay objects, carries the work of more than fifty families that employ many components of the highly labor-intensive, centuries-old practice. The white marbles of Makrana, which were used to build the Taj Mahal, are still used today; the intricate floral designs found on the objects trace their roots to the decorative flowers found on the mausoleum. Save for the use of essential carving and shaping tools, the inlay process has not been mechanized. The marble, as well as the precious and semi-precious stones, are still carved and chiseled by hand; the hand-operated pulley is still used to soften the edges of the cut stones. How much the stones must be softened to be fitted into the carved marble is purely determined by the artisan’s experience—a skill that is passed through generations of close male family members through home tutorials.

The generational nature of the marble inlay practice also means that it isn’t unusual to find a marble artisan and discover that his family has been producing and refining the craft for close to a century; in fact, many artisans that carry on the tradition today consider themselves to be the descendants of the workers that helped to build the Taj Mahal.

Rahis, the senior salesperson at Kalakriti, has been in the business for more than forty years. He used to be a craftsman himself—his role was to cut the outline of designs onto the marble to make space for the inlay—but now has transitioned to demonstrating the process to visitors and promoting the objects for sale.

“Indian marble is not fragile, like Western marble,” Rahis announced to my group. With the verve of a veteran Indian salesman, he picked up a tabletop, decorated with spiraling flowers in malachite, sapphire, carnelian, and mother of pearl, and slammed it—to my latent horror—back on the legs. “Indian marble is meant to be used, chopped on,” he continued. And as a final flourish, he opened a bottle of coca cola and poured it across the tabletop. “This,” he gestured. “Will not be a problem on Indian marble.”

Towards the end of his demonstration, Rahis lamented that it was becoming more and more difficult to recruit and train young people on their families’ crafts. “Kids don’t have the patience for it anymore,” he said, mimicking a typing motion with his hands. “They would rather be on their phones and computers.” His complaint may sound like the familiar rhetoric of our parents, but it’s indicative of a true pattern: an increasing percentage of young Indians have been chasing white-collar careers and bigger financial rewards, preferring to learn computer skills and go to universities rather than to sit down in front of a stone grinder for years to come. After all, the ability to produce such artistic riches takes patience and time to master: for an artisan to become adept at a single step in the inlay process, it may take five to ten years—a significant investment for a young person at the cusp of entering the workforce.

Still, thousands of marble inlay artisans are at work in Agra today. The Taj Mahal and the Agra Fort remain as reminders of the longevity of the inlay tradition, as well as its cultural and historical importance; and the accessibility of the craft in smaller forms certainly makes the marble inlay objects veritable treasures, in the history they embody and the reflections they may evoke. As I admired the fine, slender petals of carnelian unfurl around a gleaming marble plate, I found myself reassured that the craft will find a way to go on: humans have always found ways to create—and continue to create, despite the odds—beautiful things. And beauty never fails to inspire.