If you haven’t heard of chicha, it’s about time you do.

We’d just wrapped up an epic, authentic lunch in Bogota’s famed La Perseverancia Market. I was ready to start walking off my arepas, ajiaco, and aguardiente shots when a young man selling bottles from a small cart caught my eye.

“Maria, what’s that over there?” I curiously asked my guide.

She grinned with a glint in her eye. “That’s chicha. It’s a traditional drink here in Bogota. It’s also illegal.”

Chicha’s history has more twists and turns than a Colombian telenovela. Business interests and the government vilified the beloved beverage, eventually making it against the law to make or consume. But while chicha is still technically banned, now tourists, students, and a new generation of Colombians all continue to seek it out. For some, it’s about connecting with a new culture. For others, it’s an act of reclamation.

Daily Sustenance, Sacred Celebrations

More than a thousand years ago, the Muisca people thrived in the mountain highlands near Bogota. They were artisans and agricultural experts and had a societal hierarchy similar to those of the Mayans, Incas, and Aztecs.

“They were one of the biggest Indigenous groups,” explained Maria José Cano, founder of 321 Colombia and my guide in Bogota. “They were advanced, they had a calendar, currencies, they exchanged fabric with other Indigenous groups, they had fashion sense!”

Recommended Fodor’s Video

The Muisca made chicha from their primary food source: corn. The community’s wisest women would chew mouthfuls of the grain into a mash and spit it into a bowl. Their saliva broke down the corn’s starch and converted it to sugar, kick-starting a fermentation process that eventually produced a slightly alcoholic concoction that could be considered a bit of an acquired taste (for me, it’s a tad sour and funky—like a beer-meets-kombucha hybrid). Chicha became an integral part of the Muisca diet, providing critical albeit buzzy calories. It also took center stage in religious ceremonies.

“Chicha was used for festivals, to give thanks to Mother Earth, the stars, the growing of the food, and the start of the year,” explains Cano. “Chicha was so important for the Muisca people; there’s an incredible cultural legacy behind it.”

When Spanish colonizers seeking El Dorado arrived in Colombia in the 1500s, they subjected the Muisca people and enforced societal assimilation. The Spanish executed the Muisca’s sovereigns, replaced the peoples’ religion with Catholicism, and forced them to plant new crops. But despite the odds and oppression, the Muisca hung onto their chicha, brewing their traditional beverage in earthenware chombas and sharing it from calabash cups.

Hundreds of years later, Indigenous people came to Bogota to find work and brought chicha with them. Yet another group of Europeans took note, but this time, they leveraged the government and the press in a smear campaign in an attempt to cease its production once and for all.

A Beverage Battle in Bogota

In the late 1800s, Bogota was expanding exponentially. So were chicherías, which sprung up to support the thirsty laborer class building the capital city’s new neighborhoods, amenities, and infrastructure. One academic study shows that in 1891, Bogotá had about 120 chicherías, which cranked out nearly 25,000 liters of the beverage daily.

As workers enjoyed their chicha, perhaps during siesta or certainly after a hard day on the job, a storm was brewing at the intersection of government oversight and big business. At its epicenter: chicha and the people who enjoyed it.

“It’s important to understand that it was not only the drink,” said Catalina Muñoz Rojas, associate professor of history at the University of the Andes in Bogota. “They wanted to transform the population.”

As that population grew, so too did poverty rates. Colombia wanted to enter the global marketplace, and the pressure was on to present its capital as clean, safe, and modern. Instead of considering social reforms, Colombian politicians and the elite class decided Indigenous and working-class people and their drink of choice were the problem. Physicians spoke out, claiming chicha was unsanitary, poisonous, and harmful to workers.

A German immigrant named Emil Kopp also hopped on the anti-chicha bandwagon. In 1889, Kopp founded Bavaria Brewery in Bogota. As the government sought to control chicha consumption in the name of societal benefit, Kopp and his German business partners saw a chance to take out the competition. Bavaria began an aggressive propaganda push, placing ads in the city’s newspapers calling chicha dirty and steering people toward its “cleaner” and more hygienic bottled beer.

“They all associated chicha with a lot of evils,” explains Rojas. “It was associated with crime. They said it would make you dumb. They said if you drank chicha, it would make you violent as if drinking any other alcoholic beverage wouldn’t.”

Bavaria used shame and fear in the media and also tapped into national pride to convince people to swap their chicha for beer. The cherished revolutionary heroine Policarpa Salavarrieta—nicknamed “La Pola”—was a young seamstress turned rebel spy during Colombia’s fight for independence. On the 100th anniversary of her execution, Bavaria released its new La Pola beer, which became hugely popular. Even today, Colombians use the word “pola” as a stand-in for cerveza.

“What they couldn’t do by force—the government trying to close all the chicherías and calling it dirty—they tried to do with marketing,” said Cano. “It was sneaky, and it worked. People started drinking beer.”

The final straw for chicha? An assassination.

In 1948, presidential candidate Jorge Eliecer Gaitán was killed, touching off a period of violence in Bogota and beyond. Colombia’s Minister of Hygiene blamed chicha for the turmoil and passed a series of laws banning its production and sale. But much like moonshine during America’s Prohibition, chicha wasn’t completely gone. It simply went underground.

Making the Case for Chicha

Chicha had always been cheap and easy to make, so home brewing resumed quietly. For years, people enjoyed it in private, but eventually, public opinion shifted back toward chicha’s favor. The process was helped along by the very government that helped to ban it in the first place.

“Colombia is a country made of Indigenous people, and the Constitution of 1991 recognizes that,” Cano said. “The Muisca community is now allowed to keep its traditions, including chicha.”

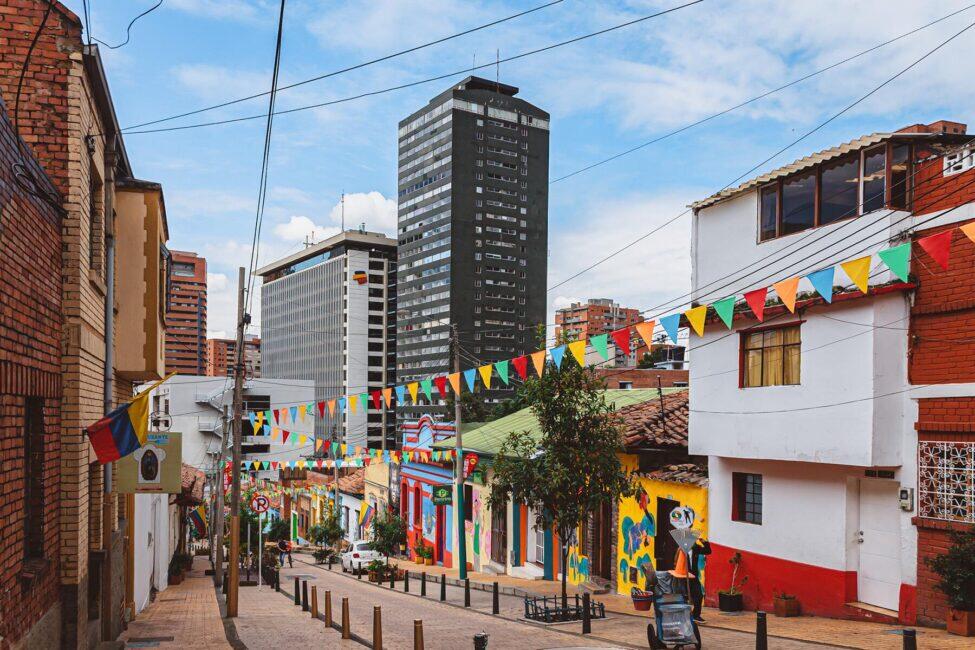

Bogota’s La Perseverancia neighborhood, where the original Bavaria Brewery once stood, founded an annual chicha festival, helping to bring the drink back out of the shadows. Thousands of people attend each year to quaff chicha in public without fear of reprisal.

Today, one can easily find chicha on offer from street vendors and at new chicherías, which are once again thriving in Bogota, despite the fact it’s still legally restricted. As the city centers its rising culinary scene on Indigenous traditions and functional food, chicha’s certainly on the comeback track. The brew that’s stood the test of time and discrimination is now celebrated by those who recognize its connections to the past and are eager to welcome it back into the present.

“Chicha is what gave the Muisca people survival,” said Cano. “It’s everything: it’s the health, the culture, and drinking it now is also our resistance.”