Walk the path of a murder and blood-thirsty mob that gave birth to the height of the Italian Renaissance.

Standing in the reverent silence of Florence’s Duomo, it’s easy to imagine the awe 15th-century citizens felt at Bruneschelli’s new and miraculous free-standing dome. Yet a very different scene filled the cathedral’s cavernous hall on Easter in 1478. As the Catholic mass moved to the sacred moment of communion for the thousands in attendance, jealous conspirators stabbed Florence’s most influential and charismatic brothers. Today, walk through the wonders of the city’s most famous sites and glimpse the murder that shaped its power and beauty.

The rival Pazzi family’s plot to overthrow the Medicis included power players from Italy’s city-states, including Pope Sixtus IV. Initially, they seemed successful. Giuliano Medici was clearly dead, stabbed so many times witnesses swore he was gone before he hit the cathedral floor. But a wounded Lorenzo Medici, the up-and-coming patron of world-famous Renaissance artists and the kingpin of the Republic of Florence’s money machine, escaped deep into the cathedral. The chaos and bloodbath that immediately followed changed not only Florence but the entire political balance of Italy from Naples to Milan.

“Wander the streets and think of the horror. Everywhere you see beauty and art that came from this family. But surviving a murder and coming out on top is what made Lorenzo ‘Il Magnifico,'” says art historian Claudia Romeo.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

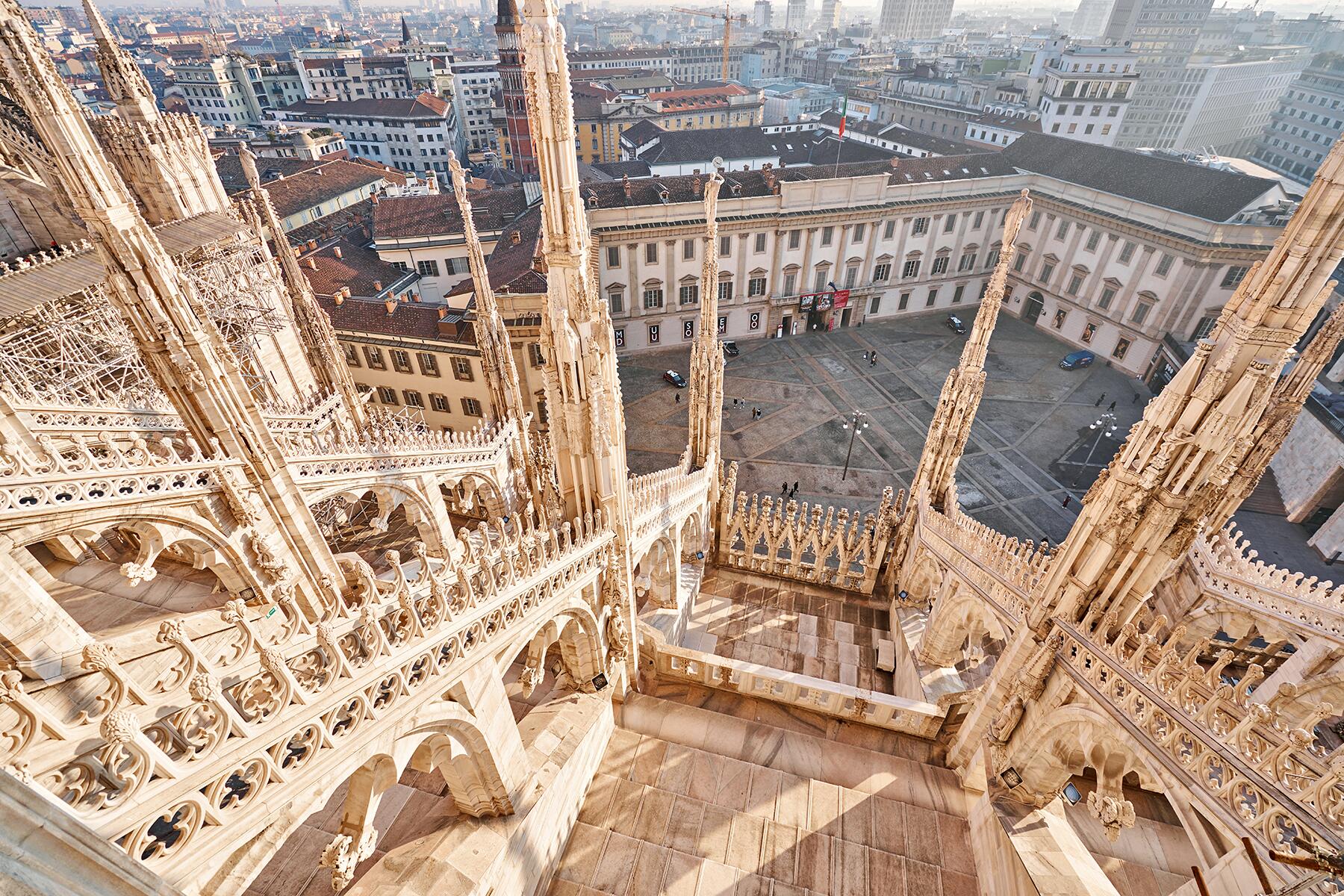

The Duomo

Florence was the bank for most of Italy and Europe during the Renaissance, with plenty of resentful debtors. No family was more influential than the relatively new house of the Medici. The men’s grandfather, Cosimo Medici, put Florence on the economic map. The proof of that soared above the city–the creation of Bruneschelli’s miraculous dome that the Medicis championed.

In an age where it wasn’t unusual to massacre your rivals at a dinner in their honor, the group set their minds to murder.

Even at 29, Lorenzo Medici was cunning and charismatic, a clever politician and poet. The people of the city loved him and his brother, Guliano. But the diminished Pazzi family was seething with jealousy and their own dangerous connections. In an age where it wasn’t unusual to massacre your rivals at a dinner in their honor, the group set their minds to murder.

It was hard to get to both brothers simultaneously, and after a few postponements, the Pazzi conspirators agreed on Easter mass at the Duomo. What might seem like sacrilege was easily soothed away–the Pope was in on the plot, and priests aided with the attack.

Near the altar, in their place of prominence, the assault started. Guiliano, 24, was stabbed nineteen times by a swarm of men. The priests attacking Lorenzo only managed to graze his throat before he was pulled away by a friend. They fled to the sacristy on the left of the altar, barring the heavy door.

Chaos erupted. Those in the back of the cathedral only knew something terrible had happened. People ran screaming into the streets. As fast as word could travel, the city’s alarm bells began to ring. Guiliano was dead. Maybe Lorenzo was too. Most citizens did not know if they, too, were under attack. In the cathedral’s piazza, where people today sip coffee, take selfies, and dodge tricky salesmen, citizens fled from their architectural wonder and scattered into the narrow streets. The worst of the bloodshed was about to erupt.

Palazzo Vecchio

While armed squads of Medici men raced to the Duomo to reinforce the family, the head of the Pazzi family, Jacopo, headed to the main piazza at the Palazzo Vecchio. Here, at the fortress turned palace turned government office, he called on the citizens of Florence to overthrow the Medici.

Yet as historian and author Lauro Martines describes in April Blood, Pazzi was doomed. The papal reinforcements did not arrive in time. And the conspirators gravely overestimated Florentine resentment towards the Medicis. The city turned on them instead.

The Palazzo Vecchio was built for protection and is as ominous as the Duomo is elegant. It’s easier to imagine carnage here. Florentines hurled the first captured conspirators out of the second-story windows. Below, where modern visitors ponder statues like Perseus beheading Medusa, the frenzied mob waited. The crowd stripped and mutilated the bodies with a gruesome rage that put those statues to shame.

More conspirators, including the Pope’s nephew, were hanged from the ramparts of the Palazzo. In the coming months, over 80 men were strung over the walls, many next to rotting bodies, according to author Miles Unger in Magnifico: The Brilliant Life and Violent Times of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Even the Bargello, today a sculptural museum with works from the Medici-sponsored artists Donatello and Michelangelo, had bodies hanging when there wasn’t enough room at the Palazzo.

Florence had resolutely chosen the Medici family. The Pazzi name was dead, stricken from records, and forbidden in conversation. The Pazzi family crest was chiseled off of the walls. Jacopo Pazzi was reburied many times as angry citizens would unearth him and prop his remains by the family door.

Pope Sixtus VI set out to exact revenge on Florence with his army. Yet, Lorenzo managed to secure an unthinkable alliance with the ruthless king of Naples, startling even the kings of Spain and France. Rome stood down.

“The Medici, who came out stronger than before, as always used arts as a tool for propaganda and self-promotion,” says Claudia Vannucci, a native Tuscan and licensed tour guide.

A Medici Walking Tour of Florence

Art, most created by the geniuses that the Medicis cultivated, had sprung up everywhere after these violent scenes. Lorenzo Medici commanded international respect as the balancing figure of Italy and no longer had to play a humble public servant. His famous “garden and grove” house sheltered and encouraged artists like Botticelli, Da Vinci, and Michelangelo. And he sent them to work in Rome, Milan, and Venice to make a point.

“He spread in Europe the image of Florence as the new Athens, the place where classical culture had come back to life,” says Vannucci. For their support, the Medici family was painted in some of the most famous works in the world.

“This was [Lorenzo’s] legacy. There have been many smart rulers in history. Few helped create some of the most defining works of art in the world,” says Romeo.

Tours like Vannucci’s reveal where infamous treason executions were painted on the walls of the Bargello palace of justice to shame the families. She’ll walk you down the “green mile” walked by wailing prisoners in their final hours. But even without a guide, if you sharpen your eyes, you will find the defaced Pazzi crests, the only surviving Pazzi mention on a corner, somber rooms in the Palazzo, and the triumphant Medicis in art and name everywhere. The bloody dramas of an era we hold as the height of beauty are still hidden in plain sight.