Glacier National Park Trip Report -- August 12-18, 2018

#1

Glacier National Park Trip Report -- August 12-18, 2018

Recently, while thinking back to our family trip to Glacier National Park in the summer of 2018, I looked it up on the Montana board and found to my surprise that there only seem to have been three trip reports posted for Glacier NP since about 2013! (Although it may also be covered in some longer accounts of trips through this portion of the northern Rockies.) So that inspired me to get busy (albeit belatedly) and do one for our trip.

Lower Grinnell Lake, Angel Wing Mountain, Upper Grinnell Falls, and the Salamander Glacier and the Garden Wall in the distance from the Upper Grinnell Lake Trail, Glacier National Park, August 17, 2018

One interesting aspect of this project once I embarked upon it is that what appears to be the last Glacier-focused trip report posted in late August 2018 was done by schlegal1 (A beautiful week in Glacier NP- Trip Report), who was there from July 28th - August 4th, 2018, very shortly before we were there from August 12th-18th. Their report mentions that they were there shortly before the Howe Ridge fire broke out, whereas our trip coincided with the first week of the fire. That makes for some interesting and instructive contrasts between our experiences.

This was a family trip: two parents who were both 61 and our two children, both now in their early twenties (but, heck, still glad to travel with us as long as we pay!). They grew up going to national parks in the west and are totally into it.

I began thinking that we needed to go see Glacier a few years back when I heard that as a result of climate change, the last of the glaciers are expected to be gone by 2030. Having always regretted that I didn’t see Berlin before the Wall fell, or the Three Gorges of the Yangtze before the dam was built, I started planning a trip in 2016 for the summer of 2017. That one had to be scrapped when my son was obligated to attend a fraternity national meeting at the same time, so we cancelled our reservations and made plans to go in August 2018.

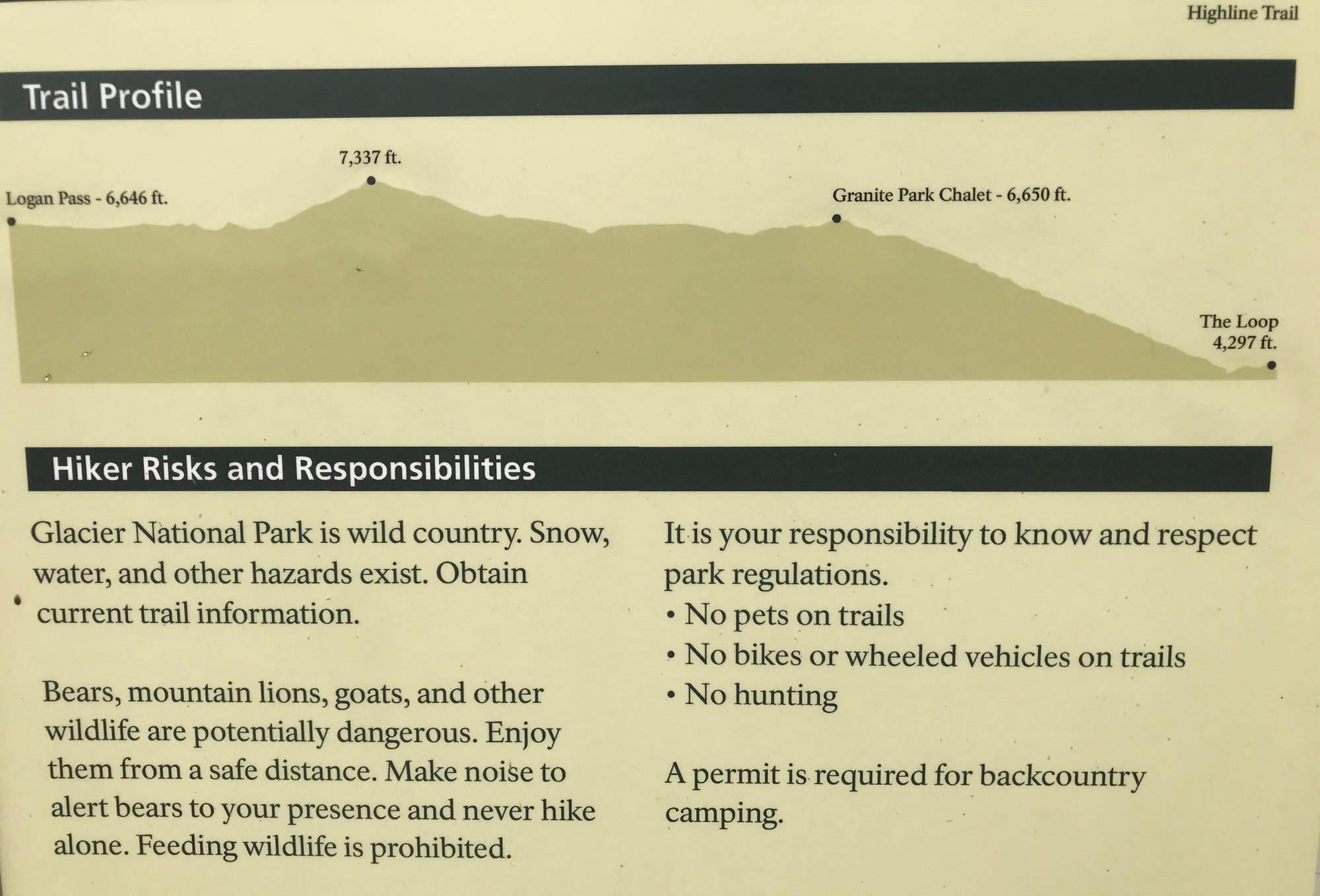

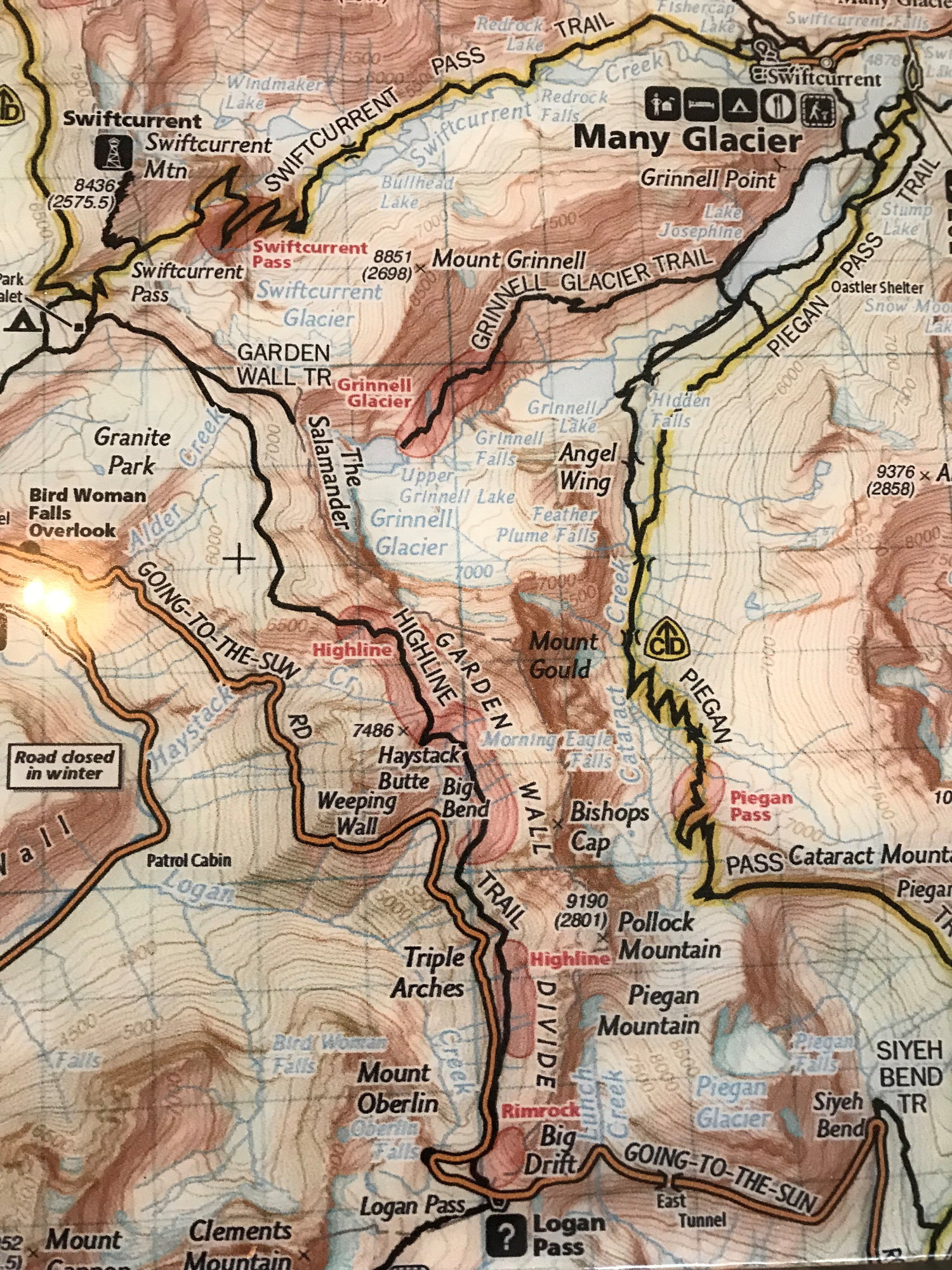

For someone like me, who prefers to stay inside the Park’s boundaries, and hopefully in one or more of the legendary Park hostelries, significant advance planning is required, and this is never more true than in the case of Glacier – particularly if you are constrained by school schedules and must go in the summer. Because of the weather, the season in Glacier is pretty short. There is only one east-west road across the Park – the legendary Going-to-the-Sun Road – and it never opens fully until around the third week of June, and sometimes not until the end of the first week of July. This is a function of deep snow at the higher elevations, in particular between the hairpin curve known as “the Loop” and Logan Pass, the main park headquarters.

The National Park Service (NPS) not surprisingly maintains a page with information on the status of Going-to-the-Sun Road – https://www.nps.gov/glac/planyourvisit/gtsrinfo.htm – and you can find out opening dates in past years by googling “going to the sun road opening date 20xx”.

Obviously, however, other portions of Going-to-the-Sun Road are open sooner than that, and the Park is probably less crowded at those times. And, ironically, although we were there in mid-August, Going-to-the-Sun Road wound up being closed basically the whole time we were there as a result of the Howe Ridge fire. The blocked portion was initially near the northern end of Lake McDonald, however, not farther up towards Logan Pass, at least not until we were about ready to leave. And we managed to cope reasonably well with the closure, although it meant a lot of extra driving during the first several days of our visit, when we were staying on the west side of the Park. Details follow below.

So, to the planning. The concessionaire for the in-Park accommodations at Glacier is Xanterra. And the way getting reservations works is that lodgings become available on the first day of the month in question one year in advance. So, since we wanted to visit Glacier in mid-August 2018, that meant that on the morning of August 1, 2017, I had to be on the phone. I started calling a few minutes before 9 a.m. eastern time that morning, and as soon as the phone lines opened, they were busy. We were on vacation elsewhere at that time, and while my family was out and about that day, I was periodically checking in with Xanterra. I finally got through at around 2 p.m. A lot of places had already been snapped up, but I was able to put together what we wanted.

It’s time for a shout-out here to a very competent Xanterra reservations agent named Kat. By a wild coincidence, she was the same one I had dealt with the year before – both in making the reservations originally and then in cancelling them! She was easy to remember because of her name and her engaging personality, and because lining up a week or so of lodging at Glacier is an involved process that can take a while (as you often have to make adjustments for already fully-booked dates) – I think we were on the phone that afternoon in August 2017 for at least half an hour (which helps to explain why it’s so hard to get through). I had pretty defined ideas of what we wanted to do, but I was open to advice and suggestions, and Kat was willing to give them based on her own experiences of the Park (so she wasn’t in some national reservations center in a place like Omaha – or if she was, she’d been to the Park and knew it pretty well).

I turned out to owe a huge debt to Kat for steering me to the Village Inn at Apgar rather than to the Lake McDonald Lodge. She couldn’t have known this, of course – she had other reasons for her recommendation – but a year later it saved us from experiencing an emergency evacuation and several nights of living like refugees in a tent camp.

The itinerary we hammered out in the end looked like this:

August 11th, Saturday – Cedar Creek Lodge in Columbia Falls, Montana (10 miles from the airport in Kalispell)

August 12th, Sunday through August 14th, Tuesday – The Village Inn at Apgar

August 15th, Wednesday through Augusta 17th, Friday – Many Glacier Hotel

August 18th, Saturday – Cedar Creek Lodge.

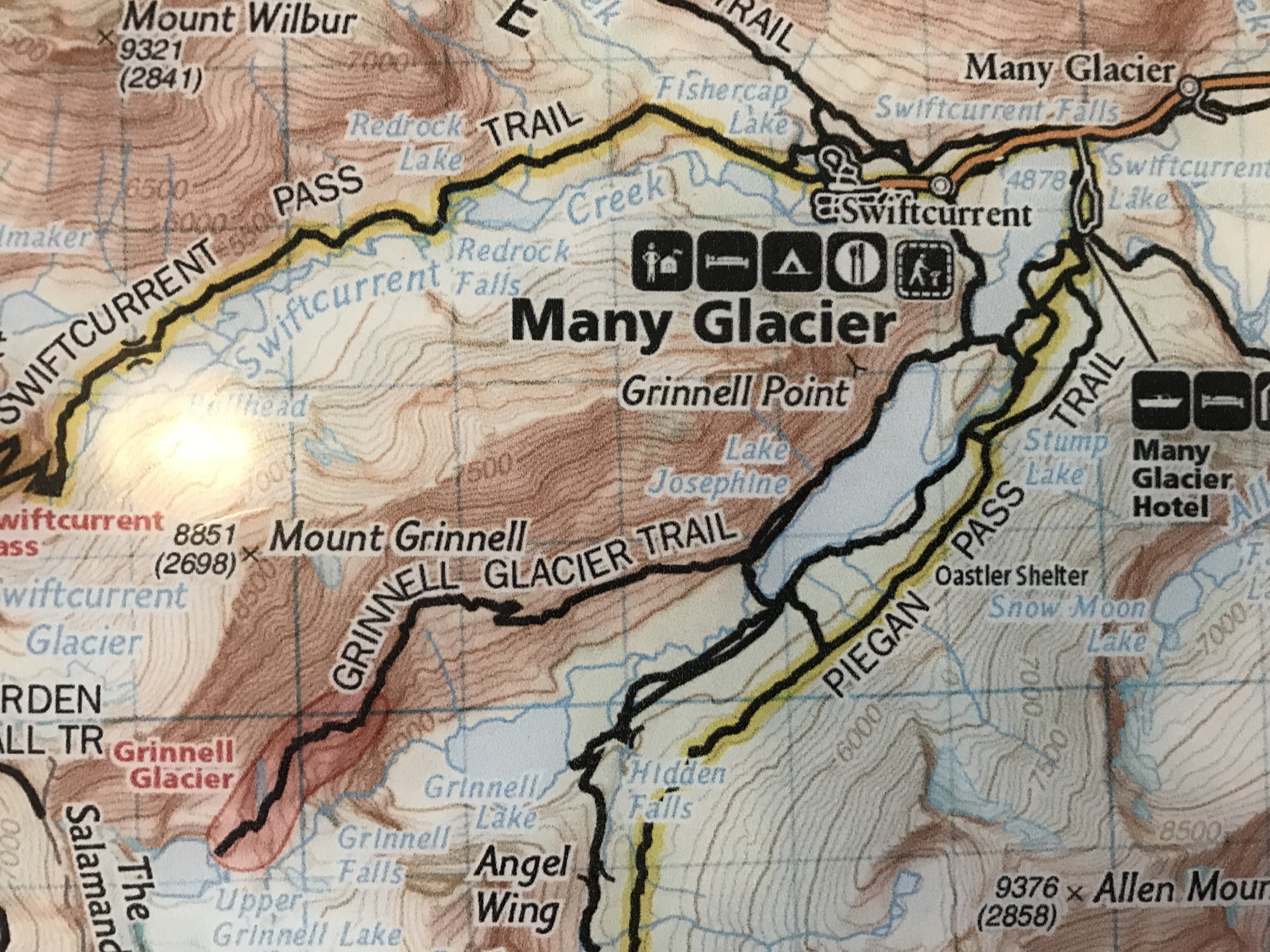

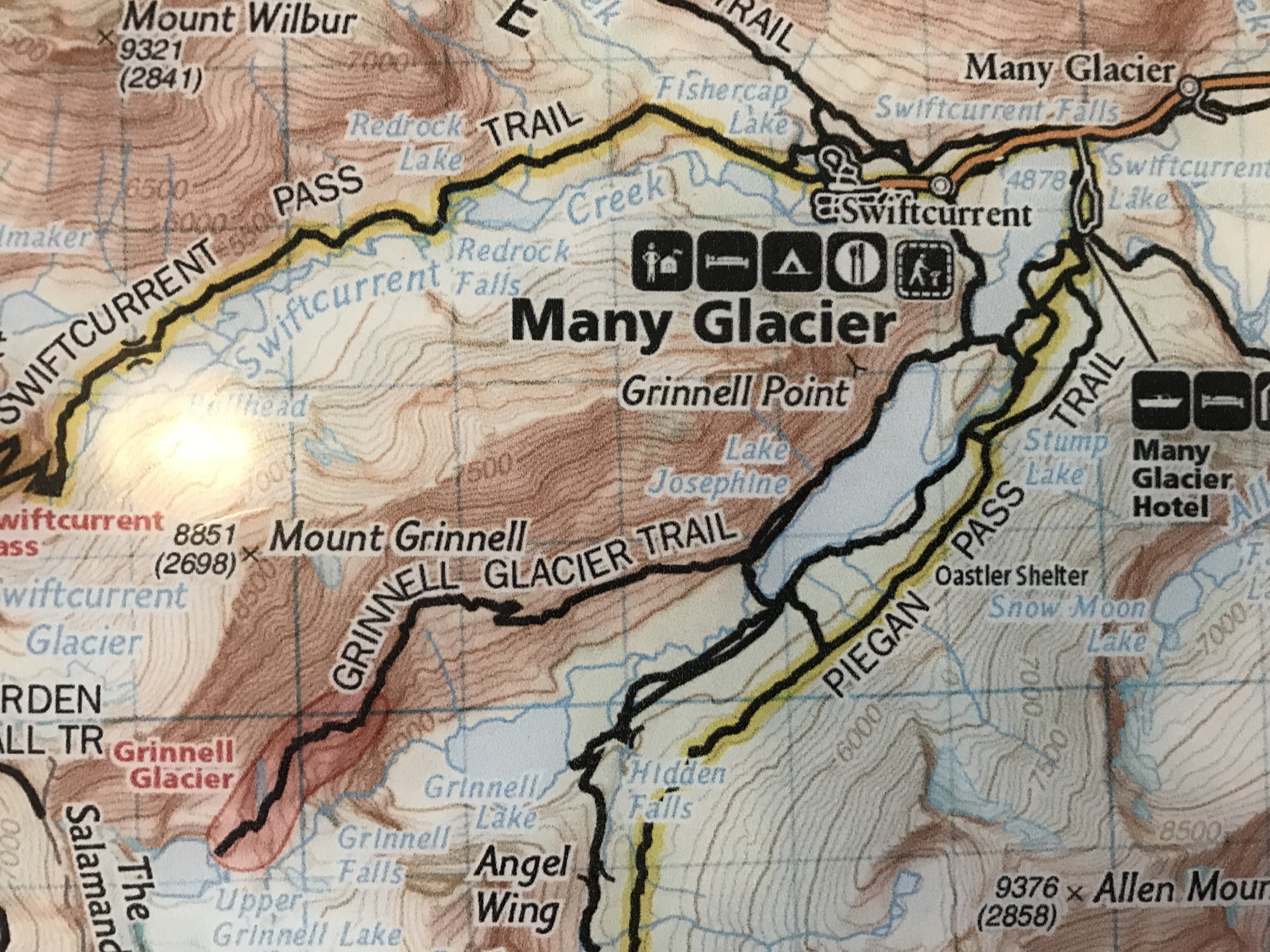

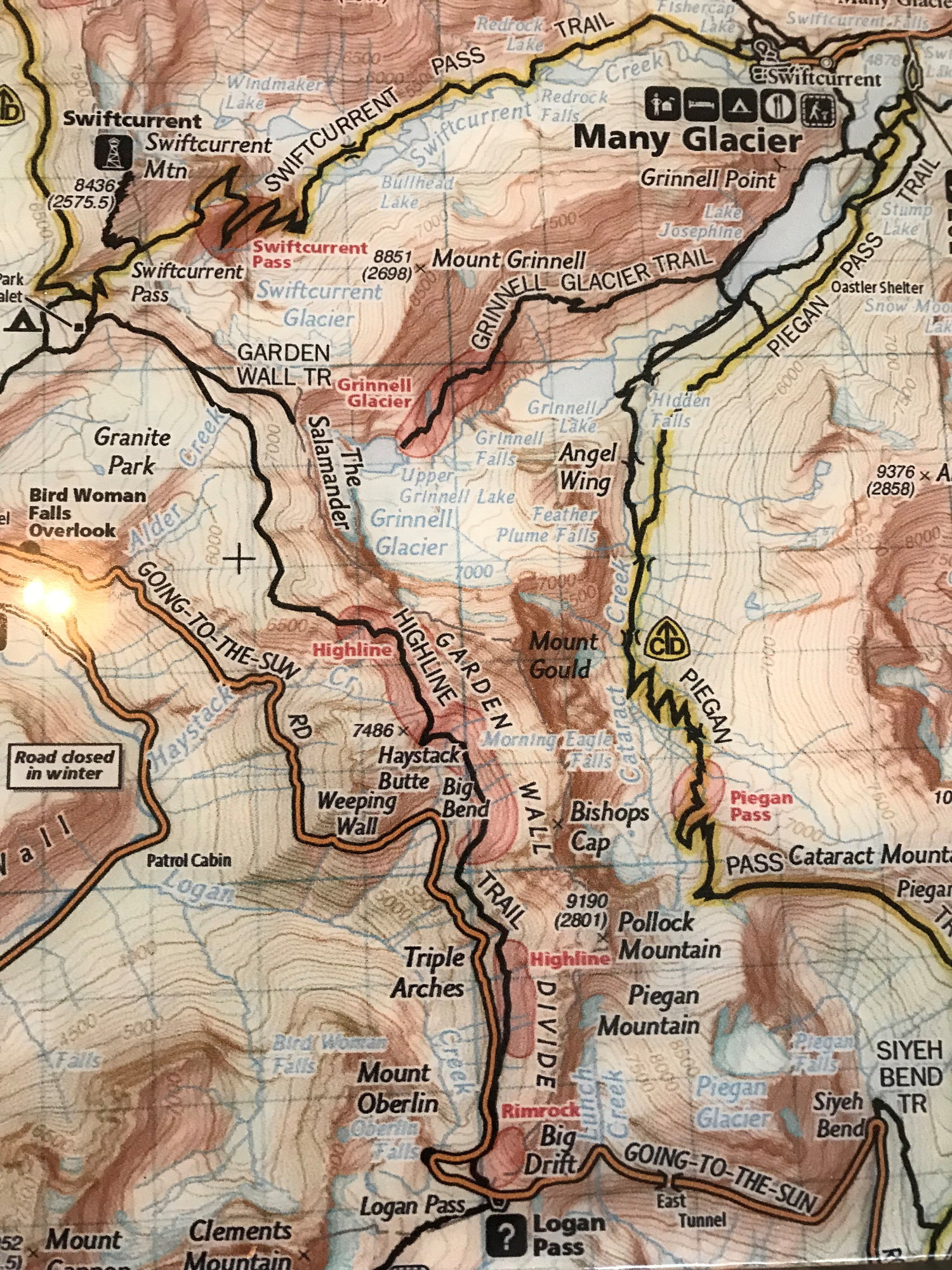

Otherwise, in terms of familiarizing myself with the Park and what we wanted to see, we relied on the Fodor’s boards, of course, and on the superb Moon Guide to Glacier (Becky Lomax, author), with further back up from Lonely Planet’s Guide to Banff, Jasper, and Glacier and the Falcon Guide entitled “Best Easy Day Hikes in Glacier and Waterton Lakes National Parks.” The Moon Guide is around 350 pages long and has great trail maps, laid out on top of contour maps. I can’t recommend it too highly.

So that’s it for the background and preparation. In the next post: the dramatic beginning of our trip!

Lower Grinnell Lake, Angel Wing Mountain, Upper Grinnell Falls, and the Salamander Glacier and the Garden Wall in the distance from the Upper Grinnell Lake Trail, Glacier National Park, August 17, 2018

One interesting aspect of this project once I embarked upon it is that what appears to be the last Glacier-focused trip report posted in late August 2018 was done by schlegal1 (A beautiful week in Glacier NP- Trip Report), who was there from July 28th - August 4th, 2018, very shortly before we were there from August 12th-18th. Their report mentions that they were there shortly before the Howe Ridge fire broke out, whereas our trip coincided with the first week of the fire. That makes for some interesting and instructive contrasts between our experiences.

This was a family trip: two parents who were both 61 and our two children, both now in their early twenties (but, heck, still glad to travel with us as long as we pay!). They grew up going to national parks in the west and are totally into it.

I began thinking that we needed to go see Glacier a few years back when I heard that as a result of climate change, the last of the glaciers are expected to be gone by 2030. Having always regretted that I didn’t see Berlin before the Wall fell, or the Three Gorges of the Yangtze before the dam was built, I started planning a trip in 2016 for the summer of 2017. That one had to be scrapped when my son was obligated to attend a fraternity national meeting at the same time, so we cancelled our reservations and made plans to go in August 2018.

For someone like me, who prefers to stay inside the Park’s boundaries, and hopefully in one or more of the legendary Park hostelries, significant advance planning is required, and this is never more true than in the case of Glacier – particularly if you are constrained by school schedules and must go in the summer. Because of the weather, the season in Glacier is pretty short. There is only one east-west road across the Park – the legendary Going-to-the-Sun Road – and it never opens fully until around the third week of June, and sometimes not until the end of the first week of July. This is a function of deep snow at the higher elevations, in particular between the hairpin curve known as “the Loop” and Logan Pass, the main park headquarters.

The National Park Service (NPS) not surprisingly maintains a page with information on the status of Going-to-the-Sun Road – https://www.nps.gov/glac/planyourvisit/gtsrinfo.htm – and you can find out opening dates in past years by googling “going to the sun road opening date 20xx”.

Obviously, however, other portions of Going-to-the-Sun Road are open sooner than that, and the Park is probably less crowded at those times. And, ironically, although we were there in mid-August, Going-to-the-Sun Road wound up being closed basically the whole time we were there as a result of the Howe Ridge fire. The blocked portion was initially near the northern end of Lake McDonald, however, not farther up towards Logan Pass, at least not until we were about ready to leave. And we managed to cope reasonably well with the closure, although it meant a lot of extra driving during the first several days of our visit, when we were staying on the west side of the Park. Details follow below.

So, to the planning. The concessionaire for the in-Park accommodations at Glacier is Xanterra. And the way getting reservations works is that lodgings become available on the first day of the month in question one year in advance. So, since we wanted to visit Glacier in mid-August 2018, that meant that on the morning of August 1, 2017, I had to be on the phone. I started calling a few minutes before 9 a.m. eastern time that morning, and as soon as the phone lines opened, they were busy. We were on vacation elsewhere at that time, and while my family was out and about that day, I was periodically checking in with Xanterra. I finally got through at around 2 p.m. A lot of places had already been snapped up, but I was able to put together what we wanted.

It’s time for a shout-out here to a very competent Xanterra reservations agent named Kat. By a wild coincidence, she was the same one I had dealt with the year before – both in making the reservations originally and then in cancelling them! She was easy to remember because of her name and her engaging personality, and because lining up a week or so of lodging at Glacier is an involved process that can take a while (as you often have to make adjustments for already fully-booked dates) – I think we were on the phone that afternoon in August 2017 for at least half an hour (which helps to explain why it’s so hard to get through). I had pretty defined ideas of what we wanted to do, but I was open to advice and suggestions, and Kat was willing to give them based on her own experiences of the Park (so she wasn’t in some national reservations center in a place like Omaha – or if she was, she’d been to the Park and knew it pretty well).

I turned out to owe a huge debt to Kat for steering me to the Village Inn at Apgar rather than to the Lake McDonald Lodge. She couldn’t have known this, of course – she had other reasons for her recommendation – but a year later it saved us from experiencing an emergency evacuation and several nights of living like refugees in a tent camp.

The itinerary we hammered out in the end looked like this:

August 11th, Saturday – Cedar Creek Lodge in Columbia Falls, Montana (10 miles from the airport in Kalispell)

August 12th, Sunday through August 14th, Tuesday – The Village Inn at Apgar

August 15th, Wednesday through Augusta 17th, Friday – Many Glacier Hotel

August 18th, Saturday – Cedar Creek Lodge.

Otherwise, in terms of familiarizing myself with the Park and what we wanted to see, we relied on the Fodor’s boards, of course, and on the superb Moon Guide to Glacier (Becky Lomax, author), with further back up from Lonely Planet’s Guide to Banff, Jasper, and Glacier and the Falcon Guide entitled “Best Easy Day Hikes in Glacier and Waterton Lakes National Parks.” The Moon Guide is around 350 pages long and has great trail maps, laid out on top of contour maps. I can’t recommend it too highly.

So that’s it for the background and preparation. In the next post: the dramatic beginning of our trip!

#2

"In the next post: the dramatic beginning of our trip!"

OOH - A cliff hanger

Really looking forward to your detailed report -- I've been to many of the NPs out here but never to Glacier and it is starting to be on my radar . . .

OOH - A cliff hanger

Really looking forward to your detailed report -- I've been to many of the NPs out here but never to Glacier and it is starting to be on my radar . . .

#3

Our Trip Begins: August 11th-12th, 2018

August 11th, Saturday:

We left our home in Baltimore for BWI Airport at 1:45, flew through Denver and changed planes there, catching a flight to Glacier International Airport in Kalispell, Montana and arriving there around 9:30 p.m. local time (which was after midnight in terms of our body clocks). Once we picked up our rental car, it was only about a 10-mile drive to the Cedar Creek Lodge in Columbia Falls, which in turn is about 20 miles from the west entrance to Glacier NP. The Cedar Creek Lodge is also owned by Xanterra (or clearly has a co-operative relationship with it, as you can make reservations through them and they advertise specials for it, especially in the shoulder season). It is pretty new and upscale, with a woodsy-ski lodge feel about it (see photo below). It also had the last queen-size beds we would see until we returned to it a week later for our final night before flying out.

The Cedar Creek Lodge, with our rental car in the foreground

I said in my previous post that I love staying in classic Park Service hostelries inside the Park boundaries. Unfortunately, my wife often does not. She did really like Many Glacier Lodge, but she hated the Village Inn at Apgar where we stayed for the next several nights. She would have much preferred spending all of our time on the west side of the Park at the Cedar Creek Lodge. From my perspective, the additional 40-mile round-trip drive each day to and from the Park entrance was a real disincentive, and waking up and being able to step out your front door and look up Lake McDonald towards the mountains was another huge plus for the Village Inn. But not everyone will see it that way. The Cedar Creek Lodge has an outdoor pool and a hot tub, which the Village Inn does not, and those amenities (along with its modernity) may be especially significant for families. Conversely, the views, the surroundings, and the immediate access to kayaks, canoes, and swimming in a lake at Apgar may matter more to others.

August 12th, Sunday:

The Cedar Creek Lodge offered an excellent breakfast as part of the room charge the next morning. (I think the room charge was around $280/night, but all four of us were able to stay in one room, so when you factored four breakfasts in as well, that wasn’t too bad). While eating breakfast, I looked up and saw a couple we knew from Baltimore walking through the lobby – one of a series of remarkable “small world” encounters we’ve had on vacation trips over the past several years. They were just about to leave for the airport, having come up for a family reunion. They told us that the weather had been beastly hot over the previous several days, even breaking 100 degrees one day, but that projections were for more comfortable temperatures and beautiful weather over the week ahead – “So you’re getting here at a great time!” Well . . . they were right about the temperatures.

Our first order of business was a whitewater rafting trip on the Flathead River, which forms much of the western border of Glacier NP, so we put on our swimsuits and checked out of the hotel before driving to West Glacier to find the offices of the Glacier Raft Company. From there, we were transported in buses about 6 miles south of town along Highway 2 – a drive we would become extremely familiar with over the next several days – to the put-in point at Moccasin Creek. We shared a raft with another family of four and our guide Sydney, who was a nursing student at the University of Montana (Missoula) in the rafting off-season. She was skilled and knowledgeable and good company throughout the trip.

Whitewater rafting on the Flathead River (yes, there is more whitewater than this photo, taken at the very end of the trip, indicates)

The water in the Flathead is somewhat low in August – perhaps especially after a week of days with temperatures in the high 90's – so the ratings of the rapids throughout this trip ranged from Class 1-3, although there was one Sydney described as having “challenging hydraulics” that perhaps edged into a Class 4. The Northern Pacific railroad tracks run along the river for much of your course, while Highway 2 is on a shelf a hundred feet or more above you, so you can’t say this is a completely bucolic experience. But it was enjoyable, and the cold water (50 degrees) kept it quite pleasant at the bottom of the canyon. The ultimate take-out point (you float north) is the modern bridge that connects West Glacier with the Park entrance. From there, we were able to walk over to the raft company’s offices and change into our clothes. We got a late lunch at a restaurant across the street at around 3:30, then drove into the park and looked through the Visitor Center there briefly before heading over (no more than a mile) to the Village Inn at Apgar at the south end of Lake McDonald to check in for our three-night stay.

The Village Inn at Apgar

The Village Inn looks like – and is – a somewhat rustic 1950's motor inn, built in 1956, the year of my birth. But it was renovated in 2015, so think of it as a spruced-up time capsule. We had two rooms on the upper (second) floor. The view up Lake McDonald from the balcony/corridor outside our rooms was spectacular, with imposing mountains in the distance – and also a single column of smoke from the northwest side of the upper end of the lake, a place called Howe Ridge. I think we’d first heard about it at check-in – the results of a lightning strike the day before. It wasn’t presented as a big deal – 50 acres or so, in an area that had few structures. To us, it was originally just a curiosity. We’d seen fires before at Yellowstone, anywhere from 20-50 miles away. We took some photos of the column of smoke with kayakers and canoeists on the lake in front of it in the middle distance (the ready availability of these is Apgar’s answer to the pool and the hot tub at the Cedar Creek Lodge).

Looking north up Lake McDonald from the Village Inn, with the Howe Ridge fire on the left

The Village Inn is small, and it has a nice vibe. Everyone enjoys sitting in the Adirondack chairs in front of their rooms looking out across the lake (as Kat had told me), and people chat readily and share information with new arrivals. One couple was from Lexington, Kentucky; they were revisiting scenes from their last trip to Glacier some 40 years earlier.

After relaxing for an hour, I managed to persuade the others that we should take advantage of the several hours of light remaining and go do a short trail called “The Trail of the Cedars” and then the Avalanche Creek Trail, which were about 20 miles north past the upper end of Lake McDonald off Going-to-the-Sun Road. The photos I’d seen of Avalanche Creek during my research had wowed me, and I knew it was a highly popular trail, so I thought the very late afternoon might be a really good time to do it and escape the crowds. That proved to be right . . . but there were to be some unexpected twists as well.

On the drive up Lake McDonald, we stopped at an overlook near the Sprague Creek camping area, where there was a beach along the lake’s edge that also gave us a good view across the water to the area of the Howe Ridge fire. The lake was beautiful in the late afternoon light, but as we looked towards the fire, it seemed like the smoke was heavier and closer to the water than we’d expected and – wait, aren’t those tongues of flame licking up those trees there!?! But we still thought this was just kind of exciting – after all, there was a rather broad and deep lake between us and the area that was burning – so we continued on north to the Avalanche Creek Trail parking area, getting there at about 6:10.

The first part of the trail complex in this area – the “Trail of the Cedars” – is an 0.9 mile loop, part boardwalk, part paved, and fully-wheelchair accessible – that winds through an Old Growth forest featuring three large distinctive trees –Western Red Cedar, Black Cottonwood, and Western Hemlock. We were about halfway along it when the Avalanche Creek Trail split off to the right. I was game; my wife was not. Just then a woman came along and told us that Avalanche Creek was really not to be missed, and the most stunning part of it wasn’t that much farther along in any case. Our kids’ votes in favor of continuing then carried the day.

Thank goodness for that hiker’s advice, because Avalanche Creek is stunning. As the Falcon Guide describes it: “Avalanche Gorge . . . was formed by the force of a stream cutting down through argillite beds [a type of dark red rock], creating fantastic bowls and chutes in the rock. The spray from small waterfalls provides the moisture needed to sustain the profusion of mosses that drape the rocks surrounding the gorge.” The gorge is often only a few feet wide, and you look down into it from 10-12 feet above. I knew it was one of the Park’s highlights, but seeing it surpassed my expectations.

Avalanche Creek (1)

Avalanche Creek (2)

Avalanche Creek (3)

We gradually followed the creek further upstream, past the top of the narrow cleft through which it runs to an area where it spreads out among massive boulders and is still quite scenic. Somewhere along this stretch, another hiker told us that we really should not miss continuing up the trail all the way to Avalanche Lake. So we did – after all, it was only a 4.6 mile round-trip from the parking area, and we were already well along it. We passed through an area where a micro-burst of wind had flattened trees as if smashed down by the edge of a giant hand, and then looked to the northeast up the dramatic Hidden Canyon, which ultimately leads to Hidden Lake below Logan Pass.

Hidden Canyon

At about 7:35, we emerged from the forest onto the beach at the northwestern end of Avalanche Lake. My 20-year-old son was in the lead at that point, and he called out and ran ahead to the edge of the water, where he turned back to look at me and flung his arms wide in amazement and awe. The lake occupies a huge natural amphitheater, with Bear Hat Mountain looming to the northeast, Mount Brown to the southwest, and Gunsight Mountain to the southeast, with multiple waterfalls streaming down hundreds of feet from the edge of the bowl-like cirque that holds the Sperry Glacier. Beyond that, with sunset approaching and smoke beginning to drift over from the Howe Ridge fire, the entire landscape had become suffused with a brooding rose- and copper-colored light. It was one of the most astonishing and beautiful landscapes I had ever seen in my life. I remember thinking that one of my favorite artists, the Hudson River School painter Frederick Edwin Church, would have loved it, and that with his mastery of late afternoon light, he would have been one of the few who could have done it justice.

Avalanche Lake

We spent some time taking in this sensational scene, then reluctantly turned back for the trail. There had only been a handful of other visitors there when we reached the lake, and there were no more than a couple still behind us when we left. (Later, I would be told that the beach at Avalanche Lake often has dozens of people on it in the middle of the day.) But I was now uncomfortably aware that we weren’t all that far away from sunset – it occurred at about 8:55 p.m. that day – and for part of that distance back, we would be walking through a dense and well-shaded forest that could be expected to be even darker. In the end, however, this didn’t turn out to be a problem.

We got back to the parking area at 8:40 p.m. Our car was the only one left, which felt a little ominous at first, but it was late in the day – and after all, many people don’t have lunch at 3:30 p.m. and therefore eat dinner at a reasonable hour! We started driving south down the quiet, deserted road towards the Lake McDonald Lodge. Suddenly, a succession of emergency vehicles came speeding past us going north, with blue and red lights flashing and sirens blaring. When we reached the north edge of Lake McDonald in the gathering darkness, we saw a cluster of emergency vehicles and then a string of drivers who had pulled off into the right side of the road with their emergency flashers on, while they stood beside their cars and were looking to the west. We followed their gaze, and saw that a wall of flames had now reached the water’s edge, while dense clouds of black smoke were billowing across the lake.

We kept going, and when we reached the Lake McDonald Lodge, we were greeted by a scene of pandemonium. An evacuation order had just been issued for the Lodge and the Sprague campground to the south of it, and it was utter chaos. We got past the Lodge and the campground, and just below that, we saw a police car that was heading towards us suddenly wheel across the road and block the northbound lane. We didn’t know this at the time, of course, but Going-to-the-Sun Road would stay blocked at that point for the remainder of our trip. We swung past onto the right shoulder and then continued on down to Apgar, where we found the other guests had come out of their rooms and were looking up the lake in the darkness, where a sinister red glow was lighting up the horizon.

Eddie’s Café, the only restaurant at Apgar, was closed by the time we got there, so we drove into West Glacier and found a place where we could get some sandwiches, salads and potato salad and took those back to our rooms to eat. I woke up in the middle of the night and stepped out onto the balcony outside my room, where I could still see the red glow limning the ridge line along the northwest side of the lake, as if an angry dragon was prowling on the other side.

The Howe Ridge fire from the Village Inn by night

[To Be Continued]

We left our home in Baltimore for BWI Airport at 1:45, flew through Denver and changed planes there, catching a flight to Glacier International Airport in Kalispell, Montana and arriving there around 9:30 p.m. local time (which was after midnight in terms of our body clocks). Once we picked up our rental car, it was only about a 10-mile drive to the Cedar Creek Lodge in Columbia Falls, which in turn is about 20 miles from the west entrance to Glacier NP. The Cedar Creek Lodge is also owned by Xanterra (or clearly has a co-operative relationship with it, as you can make reservations through them and they advertise specials for it, especially in the shoulder season). It is pretty new and upscale, with a woodsy-ski lodge feel about it (see photo below). It also had the last queen-size beds we would see until we returned to it a week later for our final night before flying out.

The Cedar Creek Lodge, with our rental car in the foreground

I said in my previous post that I love staying in classic Park Service hostelries inside the Park boundaries. Unfortunately, my wife often does not. She did really like Many Glacier Lodge, but she hated the Village Inn at Apgar where we stayed for the next several nights. She would have much preferred spending all of our time on the west side of the Park at the Cedar Creek Lodge. From my perspective, the additional 40-mile round-trip drive each day to and from the Park entrance was a real disincentive, and waking up and being able to step out your front door and look up Lake McDonald towards the mountains was another huge plus for the Village Inn. But not everyone will see it that way. The Cedar Creek Lodge has an outdoor pool and a hot tub, which the Village Inn does not, and those amenities (along with its modernity) may be especially significant for families. Conversely, the views, the surroundings, and the immediate access to kayaks, canoes, and swimming in a lake at Apgar may matter more to others.

August 12th, Sunday:

The Cedar Creek Lodge offered an excellent breakfast as part of the room charge the next morning. (I think the room charge was around $280/night, but all four of us were able to stay in one room, so when you factored four breakfasts in as well, that wasn’t too bad). While eating breakfast, I looked up and saw a couple we knew from Baltimore walking through the lobby – one of a series of remarkable “small world” encounters we’ve had on vacation trips over the past several years. They were just about to leave for the airport, having come up for a family reunion. They told us that the weather had been beastly hot over the previous several days, even breaking 100 degrees one day, but that projections were for more comfortable temperatures and beautiful weather over the week ahead – “So you’re getting here at a great time!” Well . . . they were right about the temperatures.

Our first order of business was a whitewater rafting trip on the Flathead River, which forms much of the western border of Glacier NP, so we put on our swimsuits and checked out of the hotel before driving to West Glacier to find the offices of the Glacier Raft Company. From there, we were transported in buses about 6 miles south of town along Highway 2 – a drive we would become extremely familiar with over the next several days – to the put-in point at Moccasin Creek. We shared a raft with another family of four and our guide Sydney, who was a nursing student at the University of Montana (Missoula) in the rafting off-season. She was skilled and knowledgeable and good company throughout the trip.

Whitewater rafting on the Flathead River (yes, there is more whitewater than this photo, taken at the very end of the trip, indicates)

The water in the Flathead is somewhat low in August – perhaps especially after a week of days with temperatures in the high 90's – so the ratings of the rapids throughout this trip ranged from Class 1-3, although there was one Sydney described as having “challenging hydraulics” that perhaps edged into a Class 4. The Northern Pacific railroad tracks run along the river for much of your course, while Highway 2 is on a shelf a hundred feet or more above you, so you can’t say this is a completely bucolic experience. But it was enjoyable, and the cold water (50 degrees) kept it quite pleasant at the bottom of the canyon. The ultimate take-out point (you float north) is the modern bridge that connects West Glacier with the Park entrance. From there, we were able to walk over to the raft company’s offices and change into our clothes. We got a late lunch at a restaurant across the street at around 3:30, then drove into the park and looked through the Visitor Center there briefly before heading over (no more than a mile) to the Village Inn at Apgar at the south end of Lake McDonald to check in for our three-night stay.

The Village Inn at Apgar

The Village Inn looks like – and is – a somewhat rustic 1950's motor inn, built in 1956, the year of my birth. But it was renovated in 2015, so think of it as a spruced-up time capsule. We had two rooms on the upper (second) floor. The view up Lake McDonald from the balcony/corridor outside our rooms was spectacular, with imposing mountains in the distance – and also a single column of smoke from the northwest side of the upper end of the lake, a place called Howe Ridge. I think we’d first heard about it at check-in – the results of a lightning strike the day before. It wasn’t presented as a big deal – 50 acres or so, in an area that had few structures. To us, it was originally just a curiosity. We’d seen fires before at Yellowstone, anywhere from 20-50 miles away. We took some photos of the column of smoke with kayakers and canoeists on the lake in front of it in the middle distance (the ready availability of these is Apgar’s answer to the pool and the hot tub at the Cedar Creek Lodge).

Looking north up Lake McDonald from the Village Inn, with the Howe Ridge fire on the left

The Village Inn is small, and it has a nice vibe. Everyone enjoys sitting in the Adirondack chairs in front of their rooms looking out across the lake (as Kat had told me), and people chat readily and share information with new arrivals. One couple was from Lexington, Kentucky; they were revisiting scenes from their last trip to Glacier some 40 years earlier.

After relaxing for an hour, I managed to persuade the others that we should take advantage of the several hours of light remaining and go do a short trail called “The Trail of the Cedars” and then the Avalanche Creek Trail, which were about 20 miles north past the upper end of Lake McDonald off Going-to-the-Sun Road. The photos I’d seen of Avalanche Creek during my research had wowed me, and I knew it was a highly popular trail, so I thought the very late afternoon might be a really good time to do it and escape the crowds. That proved to be right . . . but there were to be some unexpected twists as well.

On the drive up Lake McDonald, we stopped at an overlook near the Sprague Creek camping area, where there was a beach along the lake’s edge that also gave us a good view across the water to the area of the Howe Ridge fire. The lake was beautiful in the late afternoon light, but as we looked towards the fire, it seemed like the smoke was heavier and closer to the water than we’d expected and – wait, aren’t those tongues of flame licking up those trees there!?! But we still thought this was just kind of exciting – after all, there was a rather broad and deep lake between us and the area that was burning – so we continued on north to the Avalanche Creek Trail parking area, getting there at about 6:10.

The first part of the trail complex in this area – the “Trail of the Cedars” – is an 0.9 mile loop, part boardwalk, part paved, and fully-wheelchair accessible – that winds through an Old Growth forest featuring three large distinctive trees –Western Red Cedar, Black Cottonwood, and Western Hemlock. We were about halfway along it when the Avalanche Creek Trail split off to the right. I was game; my wife was not. Just then a woman came along and told us that Avalanche Creek was really not to be missed, and the most stunning part of it wasn’t that much farther along in any case. Our kids’ votes in favor of continuing then carried the day.

Thank goodness for that hiker’s advice, because Avalanche Creek is stunning. As the Falcon Guide describes it: “Avalanche Gorge . . . was formed by the force of a stream cutting down through argillite beds [a type of dark red rock], creating fantastic bowls and chutes in the rock. The spray from small waterfalls provides the moisture needed to sustain the profusion of mosses that drape the rocks surrounding the gorge.” The gorge is often only a few feet wide, and you look down into it from 10-12 feet above. I knew it was one of the Park’s highlights, but seeing it surpassed my expectations.

Avalanche Creek (1)

Avalanche Creek (2)

Avalanche Creek (3)

We gradually followed the creek further upstream, past the top of the narrow cleft through which it runs to an area where it spreads out among massive boulders and is still quite scenic. Somewhere along this stretch, another hiker told us that we really should not miss continuing up the trail all the way to Avalanche Lake. So we did – after all, it was only a 4.6 mile round-trip from the parking area, and we were already well along it. We passed through an area where a micro-burst of wind had flattened trees as if smashed down by the edge of a giant hand, and then looked to the northeast up the dramatic Hidden Canyon, which ultimately leads to Hidden Lake below Logan Pass.

Hidden Canyon

At about 7:35, we emerged from the forest onto the beach at the northwestern end of Avalanche Lake. My 20-year-old son was in the lead at that point, and he called out and ran ahead to the edge of the water, where he turned back to look at me and flung his arms wide in amazement and awe. The lake occupies a huge natural amphitheater, with Bear Hat Mountain looming to the northeast, Mount Brown to the southwest, and Gunsight Mountain to the southeast, with multiple waterfalls streaming down hundreds of feet from the edge of the bowl-like cirque that holds the Sperry Glacier. Beyond that, with sunset approaching and smoke beginning to drift over from the Howe Ridge fire, the entire landscape had become suffused with a brooding rose- and copper-colored light. It was one of the most astonishing and beautiful landscapes I had ever seen in my life. I remember thinking that one of my favorite artists, the Hudson River School painter Frederick Edwin Church, would have loved it, and that with his mastery of late afternoon light, he would have been one of the few who could have done it justice.

Avalanche Lake

We spent some time taking in this sensational scene, then reluctantly turned back for the trail. There had only been a handful of other visitors there when we reached the lake, and there were no more than a couple still behind us when we left. (Later, I would be told that the beach at Avalanche Lake often has dozens of people on it in the middle of the day.) But I was now uncomfortably aware that we weren’t all that far away from sunset – it occurred at about 8:55 p.m. that day – and for part of that distance back, we would be walking through a dense and well-shaded forest that could be expected to be even darker. In the end, however, this didn’t turn out to be a problem.

We got back to the parking area at 8:40 p.m. Our car was the only one left, which felt a little ominous at first, but it was late in the day – and after all, many people don’t have lunch at 3:30 p.m. and therefore eat dinner at a reasonable hour! We started driving south down the quiet, deserted road towards the Lake McDonald Lodge. Suddenly, a succession of emergency vehicles came speeding past us going north, with blue and red lights flashing and sirens blaring. When we reached the north edge of Lake McDonald in the gathering darkness, we saw a cluster of emergency vehicles and then a string of drivers who had pulled off into the right side of the road with their emergency flashers on, while they stood beside their cars and were looking to the west. We followed their gaze, and saw that a wall of flames had now reached the water’s edge, while dense clouds of black smoke were billowing across the lake.

We kept going, and when we reached the Lake McDonald Lodge, we were greeted by a scene of pandemonium. An evacuation order had just been issued for the Lodge and the Sprague campground to the south of it, and it was utter chaos. We got past the Lodge and the campground, and just below that, we saw a police car that was heading towards us suddenly wheel across the road and block the northbound lane. We didn’t know this at the time, of course, but Going-to-the-Sun Road would stay blocked at that point for the remainder of our trip. We swung past onto the right shoulder and then continued on down to Apgar, where we found the other guests had come out of their rooms and were looking up the lake in the darkness, where a sinister red glow was lighting up the horizon.

Eddie’s Café, the only restaurant at Apgar, was closed by the time we got there, so we drove into West Glacier and found a place where we could get some sandwiches, salads and potato salad and took those back to our rooms to eat. I woke up in the middle of the night and stepped out onto the balcony outside my room, where I could still see the red glow limning the ridge line along the northwest side of the lake, as if an angry dragon was prowling on the other side.

The Howe Ridge fire from the Village Inn by night

[To Be Continued]

#4

After I wrote the above post, I found a video on YouTube of the Howe Ridge fire that was filmed from the west side of Lake McDonald on the evening of Saturday, August 12th. My guess would be that the time of the filming was probably around 8:00 - 8:30, because the fire was nowhere close to this severe when we stopped to look at it from near the Sprague Campground around 6 p,m. It demonstrates the circumstances that prompted the crash evacuation of the Lake McDonald Lodge that we drove into as we returned from Avalanche Creek just before 9 p.m.

And here’s a time-lapse film of the fire’s growth on Sunday afternoon and evening that was shot by a local TV station:

And here’s a time-lapse film of the fire’s growth on Sunday afternoon and evening that was shot by a local TV station:

#5

August 13th. Monday: To the Two Medicine Area and St. Mary Lake

When I woke up this morning, my wife was already up and sitting outside in one of the armchairs on the gallery outside our rooms. She complained that her bed’s mattress was so soft she got little sleep that night. The beds were soft, although it hadn’t been a problem for the other three of us, and she did better on the two following nights. But although I liked it, we clearly won’t be staying at the Village Inn on any future trips to Glacier.

Morning at the Village Inn

I was told by the Inn’s manager that Going-to-The-Sun Road remained closed where we had seen the roadblock established the night before, which was hardly a surprise. Looking north up the lake, the whole northern half of it was now obscured by smoke, although the air remained clear thus far around Apgar. We learned that the evacuees from the Lake McDonald Lodge were now being housed in a refugee tent compound somewhere nearby that the awesomely efficient Park Service had conjured up on remarkably short notice.

The view north up Lake McDonald that morning

We had breakfast at Eddie’s Café, an informal, family-oriented establishment that is the only restaurant at Apgar. But for breakfast, in particular, it was great: hearty, classic offerings, well-prepared, and reasonable prices. I had three huge pancakes and sausages, so I started the day’s adventure well-prepared.

We set off in our rental car down Route 2 at 10:45 a.m. Because Going-to-The-Sun Road is the only east-west communication across the park, its closure meant that we would have to drive along the park’s western and southern boundaries to get over to the east side to see any major sights. (There would have been some trails we could have done by going north, but none of them were on my list and none of the park’s major attractions were up there.) So we made our objective the Two Medicine Area at the southeastern corner of the Park, a 55-mile drive away.

We got there in about an hour. Two Medicine is a valley with a couple of lakes, a number of trails, one or two waterfalls, and a surrounding girdle of mountains. As we were coming down the approach road, it looked stunning, certainly well-worth a visit: but, uh oh, what’s this long line of cars backed up from the entrance kiosk?

Distant View of the Two Medicine Area

When we finally inched up to it, we learned that owing to the limited number of parking places in this rather self-contained area of the park, they were unable to admit any other cars for some unknown period of time. So scratch that.

What would Plan B be? We drove back into East Glacier and stopped off at the Glacier Park Lodge, which we had passed by earlier. It’s another Park Service accommodation that was originally built back in 1915 by the Northern Pacific Railroad, a few years after they first managed to run a pair of tracks through these parts (more on that later). It’s built of dark, massive logs of Douglas Fir with a cathedral-like lobby and is worth stopping to see in its own right.

The Glacier Lake Lodge (1913)

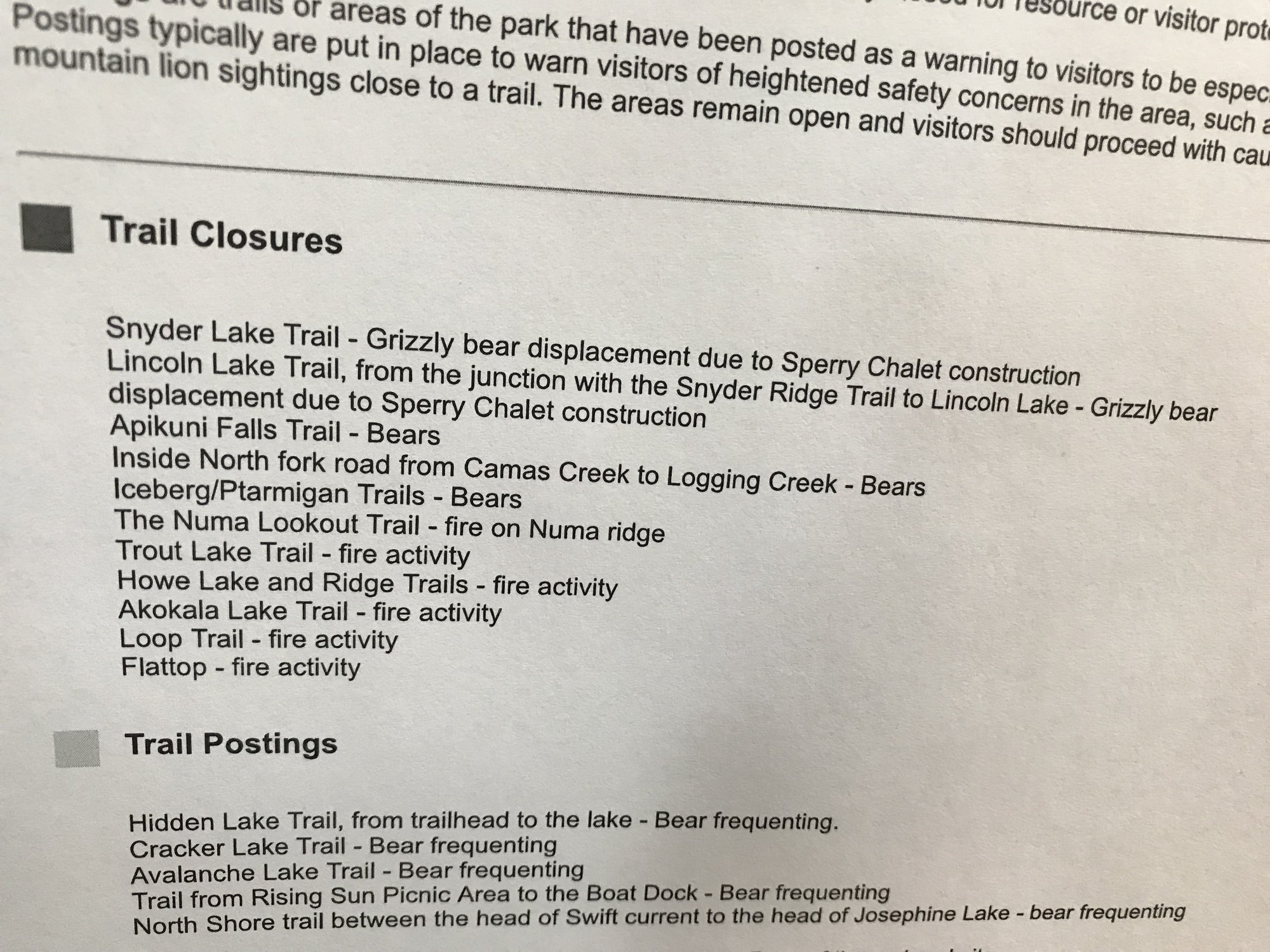

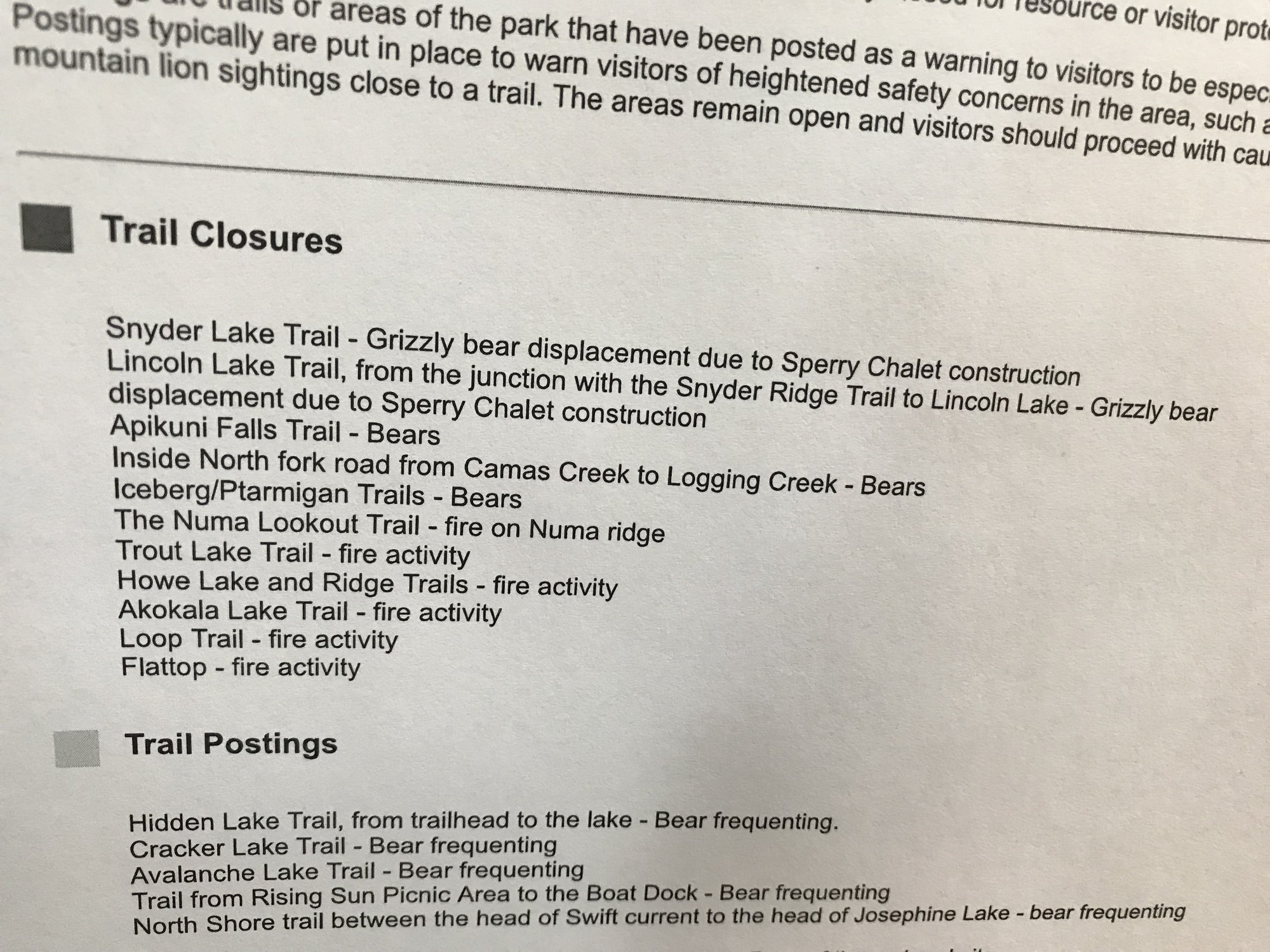

There was also a tourist information office where we could make some inquiries. One of the first things we noticed there was a page (shown below) listing all of the trails and areas around the park that were closed either to due to fire activity or bear activity. The number of the latter was a reminder that as the summer wears on and food gets exhausted at the higher elevations, the bears push down closer to the areas that are more heavily trafficked by tourists. So that’s another aspect of the natural world that you should factor into scheduling a visit to Glacier.

Notice of Trail Closings and Postings (warnings) -- and the reasons why

From the woman at the information desk, we learned that Highway 89, the most direct route north up the east side of the park towards St. Mary, was under construction, and thus it would be faster to take the longer road through Browning. This lay across the plains to the east, and we passed a grazing herd of buffalo along the way. We drove through Browning, the capital of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, and then sped along largely empty highways across the treeless hills that eventually fed us back into Highway 89 north of the construction zone. Then the St. Mary Valley came into view – a long, winding lake sandwiched between tall blue mountains – off to the west.

View west from Highway 89 towards the St. Mary Valley

Spread across the hills in the foreground of that grand vista, however, were the bare gray sticks of trees that died during a fire in 2013. And that wouldn’t be the last marks of wildfires that we would see that afternoon, for an hour or so later we were making our way through the now-regenerating landscape along the northwest side of St. Mary Lake where the Reynolds Creek Fire had raged in July 2015. Add to that the Sprague Fire east of Lake MacDonald the previous summer that destroyed the century-old Sperry Chalet, and you can see that Glacier is experiencing a major fire on average about every other year. This reflects the surprising fact that Glacier – “the crown of the continent” – has already suffered the 2 degrees centigrade temperature rise that has always been such a red flag in the climate change literature. With drier, hotter conditions – like those the week before our arrival – there is more heat lightning and, when that lightning strikes dry trees, a greater chance of fire and sometimes significant conflagrations.

We reached the NPS Information Center at the St. Mary (eastern) entrance to the Going-to-the-Sun Road at 2:30. The parking lot was full, when we first arrived, but after a couple of passes, I was able to snag a space when someone left. We caught one of the NPS shuttles heading up the road a few minutes later, planning on taking the St. Mary Falls/Virginia Falls trail at the western end of St. Mary Lake, which the shuttle bus driver assured us we would love as we were disembarking.

She was right. This trail is only 3.4 miles long, but it packs a lot of natural interest, scenic beauty, and photographic opportunities into its manageable length. First, we passed through the burn area of the Reynolds Creek fire, which after three years was already rejuvenating itself with a thick carpet of grasses, dense wild flowers (particularly purple asters), and pine seedlings. Before us to the south loomed the majestic peaks of Red Eagle, Mahtotopa, and Little Chief Mountains, while Going to the Sun Mountain looked over our shoulders from the north. The trail took us across broad, flat slabs of red argillite (also known as mudstone), which you will see throughout the park.

The first part of the Virginia Falls Trail -- that's Mahtotopa Mountain on the left, and Little Chief Mountain on the right

After about a mile of walking, we approached the St. Mary River, which still has a short distance to run before losing itself into the lake. Next, you come to a footbridge just below St. Mary Falls, a triple cascade that is only 35 feet high but that makes up for that with the compressed volume and roar of its water as it powers through a narrow cleft. The temperature was already comfortable – high 70's, low 80's – but the spray from the falls generated a refreshingly cool breeze as we crossed the bridge and then started to climb steeply on the other side as the trail continued towards Virginia Falls.

Looking down the St. Mary River towards the lake, with Mahtotopa Mountain on the right and Red Eagle Mountain in the distance

St. Mary Falls

Because Virginia Falls was still supposedly three-quarters of a mile away, I was quite surprised when after just a few minutes of climbing we came across another, higher waterfall as Virginia Creek descended in several tiers to its confluence with the St. Mary River. We all loved this waterfall, and delighted in exploring it and snapping pictures from various vantage points. We could easily have been satisfied with this as the culmination of our hike, but a passing hiker helpfully explained that delightful as this was, it was actually just some no-name waterfall that the Glacier authorities couldn’t even be troubled to christen, and that Virginia Falls – which was “not to be missed” – still lay further up the trail. So we continued on, and after passing through a mature forest that had escaped the Reynolds Creek fire, we could again hear roaring water ahead.

"No Name" Falls

Virginia Falls plummets in a sheer, unbroken drop over the edge of a cliff for some 50-60 feet, then races downhill over terraces of mudstone through a series of cascades, short falls, and pools that tempt you to further exploration. I had learned in Oregon’s waterfall country a couple of years earlier that no still photo can do justice to running water like a video does, so I made several in an effort to preserve the memory of this beautiful place that made our spirits soar like the birds coasting above us on the thermals. (Another thing that made me smile was the way each successive group of hikers arriving at the foot of Virginia Falls stepped up and offered to photograph their predecessors, after which the next group on the scene returned the favor for them.)

Virginia Falls

The view of Going-to-the-Sun Mountain as seen from the Virginia Falls Trail

We made it back to the shuttle stop by 4:45, and given the line of people ahead of us, weren’t particularly surprised that we had to wait for a second bus to come along 15-20 minutes later. Everyone seemed tired and quiet on the ride back to the NPS Visitor Center, but the views of St. Mary Lake off to the right were exceptional.

The Visitor’s Center was closed by the time we got back there, so I had to miss seeing a topographical map my daughter had been impressed by that showed the shrinking of the glaciers over the years. On the drive back south down US 89 I missed the turn for Browning, and by the time I realized my mistake, we decided just to continue on through the construction zone. This was only about three miles, and it was slow going, but once we got past it, there were wonderful views into Two Medicine Valley to the south – although the many sharp curves and bends and unprotected drops along this stretch of the highway mean that the designated driver won’t get to fully enjoy them.

We tried to get dinner at Serrano’s – a legendary Mexican place in East Glacier – but it was so mobbed when we got there (which is its normal state) that we opted to have dinner in the main dining room at the Glacier Park Lodge instead. Our waiter there was a Turk from Istanbul (and not the only one among the wait staff there). The final 60 mile drive back to Apgar up Highway 2 was something of an ordeal. I was pretty exhausted, darkness soon descended, and the road has some tight curves and steep climbs and descents, so you have to take it carefully. By the day’s end, we had driven fully 200 miles that day. But if it had been taxing, it had also been magnificent.

Morning at the Village Inn

I was told by the Inn’s manager that Going-to-The-Sun Road remained closed where we had seen the roadblock established the night before, which was hardly a surprise. Looking north up the lake, the whole northern half of it was now obscured by smoke, although the air remained clear thus far around Apgar. We learned that the evacuees from the Lake McDonald Lodge were now being housed in a refugee tent compound somewhere nearby that the awesomely efficient Park Service had conjured up on remarkably short notice.

The view north up Lake McDonald that morning

We had breakfast at Eddie’s Café, an informal, family-oriented establishment that is the only restaurant at Apgar. But for breakfast, in particular, it was great: hearty, classic offerings, well-prepared, and reasonable prices. I had three huge pancakes and sausages, so I started the day’s adventure well-prepared.

We set off in our rental car down Route 2 at 10:45 a.m. Because Going-to-The-Sun Road is the only east-west communication across the park, its closure meant that we would have to drive along the park’s western and southern boundaries to get over to the east side to see any major sights. (There would have been some trails we could have done by going north, but none of them were on my list and none of the park’s major attractions were up there.) So we made our objective the Two Medicine Area at the southeastern corner of the Park, a 55-mile drive away.

We got there in about an hour. Two Medicine is a valley with a couple of lakes, a number of trails, one or two waterfalls, and a surrounding girdle of mountains. As we were coming down the approach road, it looked stunning, certainly well-worth a visit: but, uh oh, what’s this long line of cars backed up from the entrance kiosk?

Distant View of the Two Medicine Area

When we finally inched up to it, we learned that owing to the limited number of parking places in this rather self-contained area of the park, they were unable to admit any other cars for some unknown period of time. So scratch that.

What would Plan B be? We drove back into East Glacier and stopped off at the Glacier Park Lodge, which we had passed by earlier. It’s another Park Service accommodation that was originally built back in 1915 by the Northern Pacific Railroad, a few years after they first managed to run a pair of tracks through these parts (more on that later). It’s built of dark, massive logs of Douglas Fir with a cathedral-like lobby and is worth stopping to see in its own right.

The Glacier Lake Lodge (1913)

There was also a tourist information office where we could make some inquiries. One of the first things we noticed there was a page (shown below) listing all of the trails and areas around the park that were closed either to due to fire activity or bear activity. The number of the latter was a reminder that as the summer wears on and food gets exhausted at the higher elevations, the bears push down closer to the areas that are more heavily trafficked by tourists. So that’s another aspect of the natural world that you should factor into scheduling a visit to Glacier.

Notice of Trail Closings and Postings (warnings) -- and the reasons why

From the woman at the information desk, we learned that Highway 89, the most direct route north up the east side of the park towards St. Mary, was under construction, and thus it would be faster to take the longer road through Browning. This lay across the plains to the east, and we passed a grazing herd of buffalo along the way. We drove through Browning, the capital of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, and then sped along largely empty highways across the treeless hills that eventually fed us back into Highway 89 north of the construction zone. Then the St. Mary Valley came into view – a long, winding lake sandwiched between tall blue mountains – off to the west.

View west from Highway 89 towards the St. Mary Valley

Spread across the hills in the foreground of that grand vista, however, were the bare gray sticks of trees that died during a fire in 2013. And that wouldn’t be the last marks of wildfires that we would see that afternoon, for an hour or so later we were making our way through the now-regenerating landscape along the northwest side of St. Mary Lake where the Reynolds Creek Fire had raged in July 2015. Add to that the Sprague Fire east of Lake MacDonald the previous summer that destroyed the century-old Sperry Chalet, and you can see that Glacier is experiencing a major fire on average about every other year. This reflects the surprising fact that Glacier – “the crown of the continent” – has already suffered the 2 degrees centigrade temperature rise that has always been such a red flag in the climate change literature. With drier, hotter conditions – like those the week before our arrival – there is more heat lightning and, when that lightning strikes dry trees, a greater chance of fire and sometimes significant conflagrations.

We reached the NPS Information Center at the St. Mary (eastern) entrance to the Going-to-the-Sun Road at 2:30. The parking lot was full, when we first arrived, but after a couple of passes, I was able to snag a space when someone left. We caught one of the NPS shuttles heading up the road a few minutes later, planning on taking the St. Mary Falls/Virginia Falls trail at the western end of St. Mary Lake, which the shuttle bus driver assured us we would love as we were disembarking.

She was right. This trail is only 3.4 miles long, but it packs a lot of natural interest, scenic beauty, and photographic opportunities into its manageable length. First, we passed through the burn area of the Reynolds Creek fire, which after three years was already rejuvenating itself with a thick carpet of grasses, dense wild flowers (particularly purple asters), and pine seedlings. Before us to the south loomed the majestic peaks of Red Eagle, Mahtotopa, and Little Chief Mountains, while Going to the Sun Mountain looked over our shoulders from the north. The trail took us across broad, flat slabs of red argillite (also known as mudstone), which you will see throughout the park.

The first part of the Virginia Falls Trail -- that's Mahtotopa Mountain on the left, and Little Chief Mountain on the right

After about a mile of walking, we approached the St. Mary River, which still has a short distance to run before losing itself into the lake. Next, you come to a footbridge just below St. Mary Falls, a triple cascade that is only 35 feet high but that makes up for that with the compressed volume and roar of its water as it powers through a narrow cleft. The temperature was already comfortable – high 70's, low 80's – but the spray from the falls generated a refreshingly cool breeze as we crossed the bridge and then started to climb steeply on the other side as the trail continued towards Virginia Falls.

Looking down the St. Mary River towards the lake, with Mahtotopa Mountain on the right and Red Eagle Mountain in the distance

St. Mary Falls

Because Virginia Falls was still supposedly three-quarters of a mile away, I was quite surprised when after just a few minutes of climbing we came across another, higher waterfall as Virginia Creek descended in several tiers to its confluence with the St. Mary River. We all loved this waterfall, and delighted in exploring it and snapping pictures from various vantage points. We could easily have been satisfied with this as the culmination of our hike, but a passing hiker helpfully explained that delightful as this was, it was actually just some no-name waterfall that the Glacier authorities couldn’t even be troubled to christen, and that Virginia Falls – which was “not to be missed” – still lay further up the trail. So we continued on, and after passing through a mature forest that had escaped the Reynolds Creek fire, we could again hear roaring water ahead.

"No Name" Falls

Virginia Falls plummets in a sheer, unbroken drop over the edge of a cliff for some 50-60 feet, then races downhill over terraces of mudstone through a series of cascades, short falls, and pools that tempt you to further exploration. I had learned in Oregon’s waterfall country a couple of years earlier that no still photo can do justice to running water like a video does, so I made several in an effort to preserve the memory of this beautiful place that made our spirits soar like the birds coasting above us on the thermals. (Another thing that made me smile was the way each successive group of hikers arriving at the foot of Virginia Falls stepped up and offered to photograph their predecessors, after which the next group on the scene returned the favor for them.)

Virginia Falls

The view of Going-to-the-Sun Mountain as seen from the Virginia Falls Trail

We made it back to the shuttle stop by 4:45, and given the line of people ahead of us, weren’t particularly surprised that we had to wait for a second bus to come along 15-20 minutes later. Everyone seemed tired and quiet on the ride back to the NPS Visitor Center, but the views of St. Mary Lake off to the right were exceptional.

The Visitor’s Center was closed by the time we got back there, so I had to miss seeing a topographical map my daughter had been impressed by that showed the shrinking of the glaciers over the years. On the drive back south down US 89 I missed the turn for Browning, and by the time I realized my mistake, we decided just to continue on through the construction zone. This was only about three miles, and it was slow going, but once we got past it, there were wonderful views into Two Medicine Valley to the south – although the many sharp curves and bends and unprotected drops along this stretch of the highway mean that the designated driver won’t get to fully enjoy them.

We tried to get dinner at Serrano’s – a legendary Mexican place in East Glacier – but it was so mobbed when we got there (which is its normal state) that we opted to have dinner in the main dining room at the Glacier Park Lodge instead. Our waiter there was a Turk from Istanbul (and not the only one among the wait staff there). The final 60 mile drive back to Apgar up Highway 2 was something of an ordeal. I was pretty exhausted, darkness soon descended, and the road has some tight curves and steep climbs and descents, so you have to take it carefully. By the day’s end, we had driven fully 200 miles that day. But if it had been taxing, it had also been magnificent.

#6

August 14th, Tuesday: Logan Pass and Marvelous Megafauna

This was our last full day at Apgar, which meant doing another 200-mile round trip to get to the east side of the park. We had breakfast again at Eddie’s Café (loved the chicken-fried steak, as did my son) and managed to get on Highway 2 by 10:00. In pursuit of some variety, we stopped along the way (milepost 182.6) to hike down to a cliff face above the Flathead River called the Goat Lick, which our Moon Guide indicated attracts mountain goats, but we didn’t see any. (Much later, I saw that in the guide’s separate section on wildlife, the author reported that goats are most likely to be seen at the Goat Lick in the late spring.) As the day developed, however, our unsuccessful pursuit of mountain goats at the Goat Lick would prove to have been completely superfluous.

We also stopped at Silver Stairs Falls (milepost 188.2), which the Moon Guide said “tumbl[es] thousands of feet” (?? Angel Falls, move over?) and is supposed to be pretty dramatic in June and July when the snow runoff is at its peak. But by mid-August, after many 90-degree and a few 100-degree days, the rocky cliff looming above us was merely shaking off drops of water like a dog after a bath.

Silver Stairs Falls, at low water

With these stops, we reached the Two Medicine entrance area at almost the same time we had the day before, and with the same result: no entry. However, I have encountered some suggestions in on-line videos that given the limited parking capacity in Two Medicine, this is capable of happening in Glacier’s peak tourist season even without a fire blocking Going-to-the-Sun Road. Moral: if you want to see Two Medicine, get there early (which is actually pretty good advice for Glacier in general).

We made a pit stop by the Glacier Lake Lodge, then followed our trail of the day before back through Browning. This time, however, we stopped to see the Museum of the Plains Indian, a federal government economic development effort from the 1940's that, while it lacked modern-day museum display razzle-dazzle, we nevertheless found informative and interesting. Its coverage extended beyond the Blackfeet to other plains tribes as well, and was heavy on religion, costume, tools, and hunting techniques and equipment. Photographs were not allowed, however, so I have none to offer.

After the museum, we stopped by the tribal arts and crafts store. The Blackfeet are known for beadwork, so I picked up an elaborate piece depicting a bear silhouetted against the sky that today hangs from one of the shelves in my man cave.

We then continued along our route from the day before back to Highway 89 and on up towards the St. Mary entrance and the eastern end of Going-to-the-Sun Road. The day before, the vistas of the St. Mary Valley had prompted us to pull over repeatedly for photos, but today those views were significantly compromised by the thickening smoke drifting over the Continental Divide from Howe Ridge.

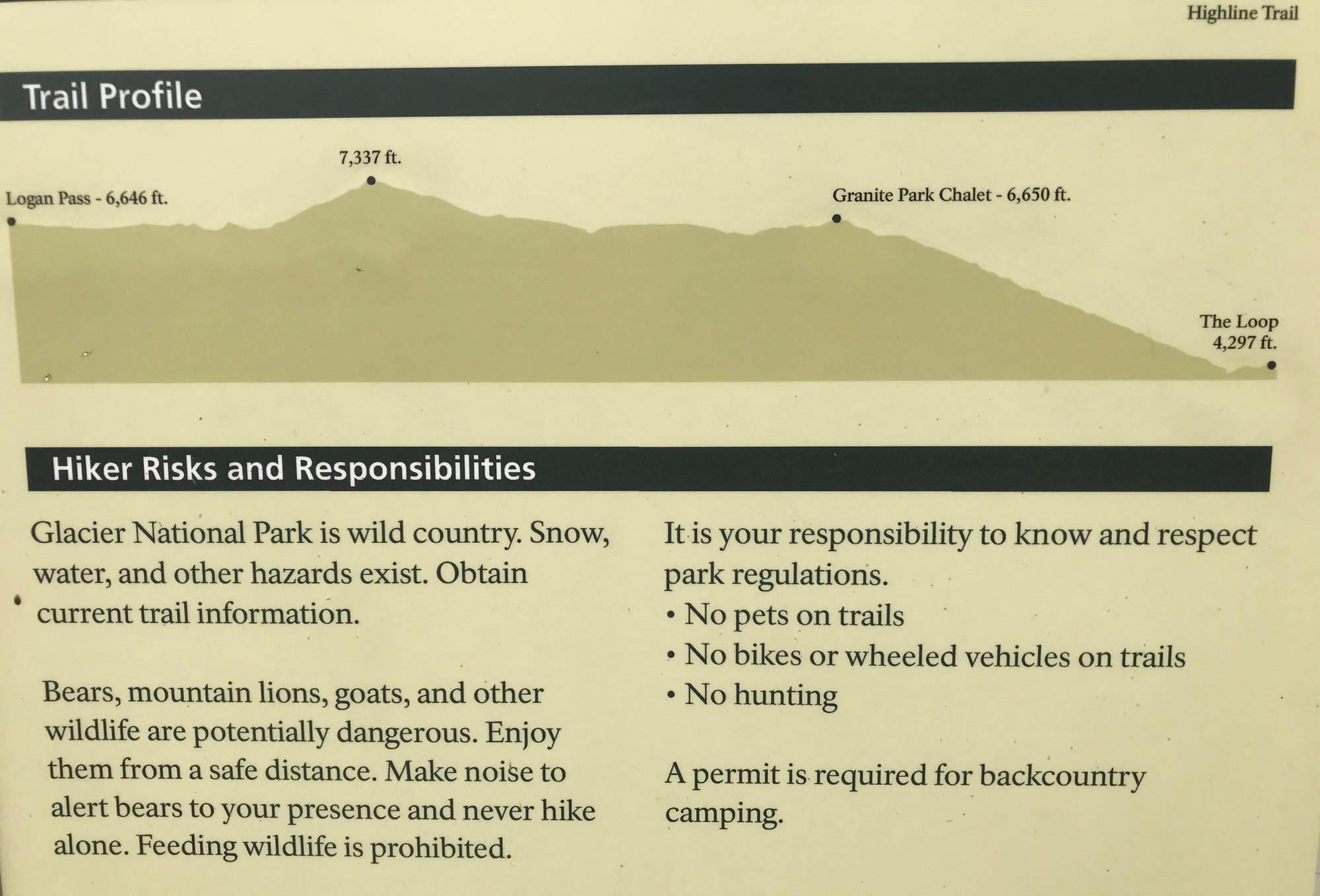

I had assumed we would stop at the NPS Visitor Center at St. Mary and catch the shuttle again, but my family members wanted to go for it and drive, so that’s what we did. As soon as we approached the first parking area, it was clear that the smoke was keeping people away. When we reached the parking area at Logan Pass up at the Continental Divide, we had no problem at all finding space – but it was also evident why this could normally be a very challenging proposition. As you might expect of a parking area located at the top of a mountain pass (with an elevation of 6,646 feet, some 2,200 feet higher than St. Mary, and 3,400 feet above Lake McDonald), there just isn’t that much flat space up there. The Moon Guide said that most days you need to be there before 8:30 to be confident of getting a space. So at least we got that one benefit from the fire.

The parking lot at Logan Pass, late afternoon

We walked through the NPS Visitor Center in the pass and enjoyed its diverse collection of stuffed wild animals. Next, we decided to stretch our legs on the highly popular Hidden Lake Trail, which runs 1.5 miles across the alpine tundra to the Hidden Lake Overlook. This is pretty surely the most heavily-trafficked trail in the park, but it wasn’t bad by this point in the afternoon. It starts off as a boardwalk and initially runs through an area called the Hanging Gardens that is dense with mosses and wildflowers watered by streaming rivulets of snow melt coming down from Mount Clements, which looms above you to the right of the trail. There were subalpine daisies, indian paintbrush, shrubby purple penstemon, and stemless goldenweed.

Stemless Goldenweed

Shrubby Purple Penstemon

Eventually, at the crest of the trail, you enter into a belt of fir trees just above the overlook. Just as we passed a marker for the Continental Divide at mile 1.2, we looked to the right and saw a mother mountain goat and her calf resting comfortably on the ground only about 75 feet away! We paused to take photos, but they were utterly unfazed by our proximity; the mother had a tracking collar around her neck, so presumably she is somewhat accustomed to the human presence. We remembered how back in 2016 we had been thrilled so see four mountain goats moving across a steep slope in Denali, probably at least a full mile away and looking like the tiny white aphids I occasionally see on garden plants. And now, there they were – making us all feel a little silly about our hike to the Goat Lick a few hours before.

Mother mountain goat and calf

More was to come. We reached the overlook and took in the view of Hidden Lake below us – so named, I presume, because you cannot see if from Logan Pass – but today it was further veiled by a soft layer of gray smoke. It was another 1.5 miles down to the lake, making for a 3-mile round trip, and from both a photographic and a breathing standpoint, there was clearly no reason to proceed any farther. When my daughter and I climbed a bluff behind the overlook to take some pictures of the surrounding peaks, which were still raising their summits above the smoke, we encountered a male mountain goat moving through the trees who likewise seemed completely indifferent to us (he, too, was wearing a tracking collar). He ultimately decided to settle down and make himself comfortable next to a fir tree only about 20 feet away from us: “Don’t mind me,” his manner seemed to say. More pictures.

Mountain goat # 2

Then we headed back up the trail towards to Continental Divide – where another, younger male mountain goat, unadorned by a tracking collar this time, came ambling down the trail in our direction. We stopped, and so he detoured off the trail (“I know the drill”) and passed by us through the fir trees along the edge of the trail as he continued on his way. A short distance below us, he started to cross the trail and then paused, looking down it towards the Hidden Lake Overlook. This caused an approaching solo hiker who came into sight a moment later to suddenly startle and pull himself up short. The goat contemplated him for a moment, then almost shrugged – “Seen one hiker, you’ve seen ‘em all” – and ambled on his way. These successive encounters made it very easy to decide which stuffed animal we would get for my grand-niece when we got back to the Visitor’s Center.

Mountain goat # 3

Stuffed animal assortment, Logan Pass Visitor Center

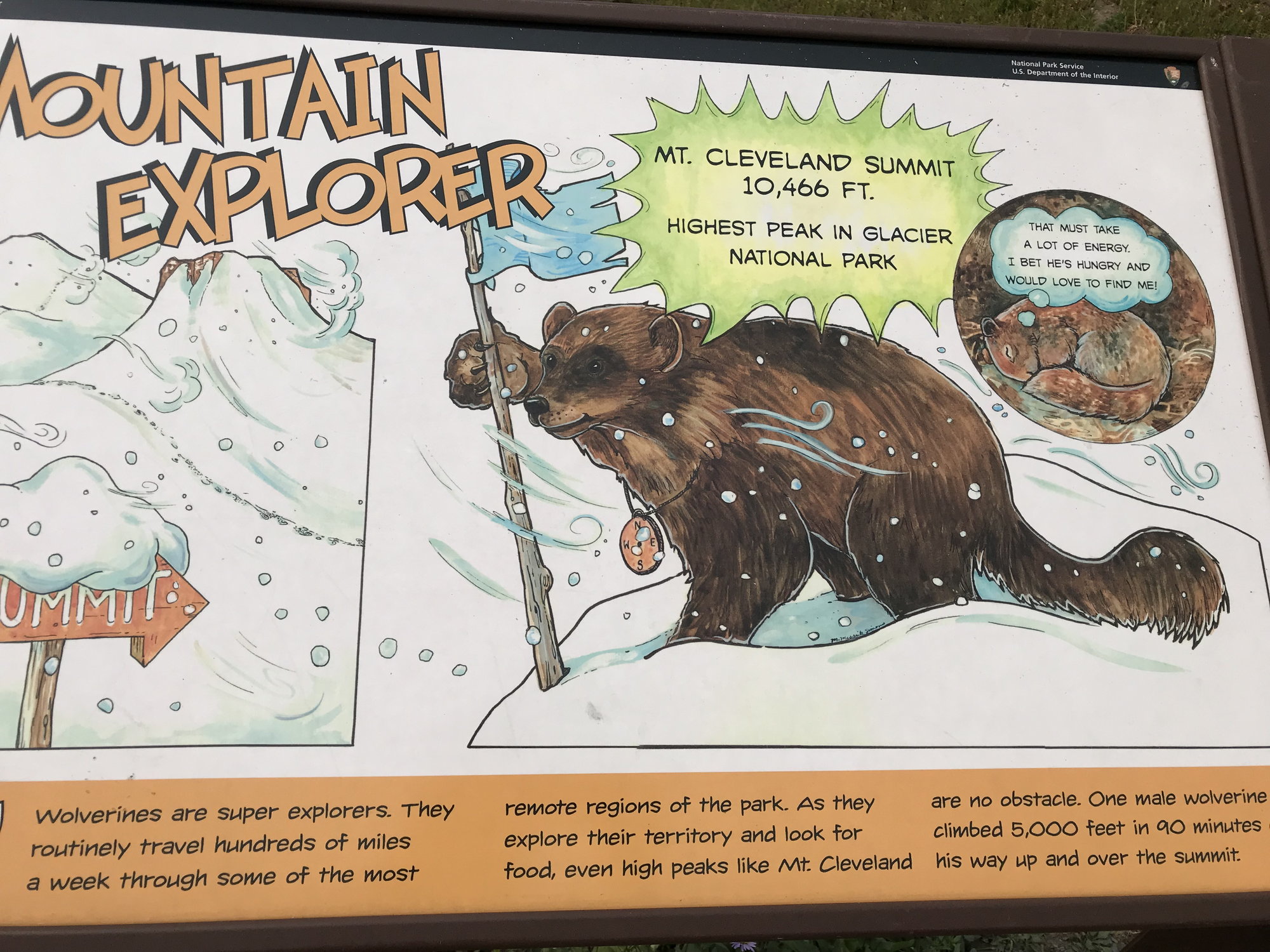

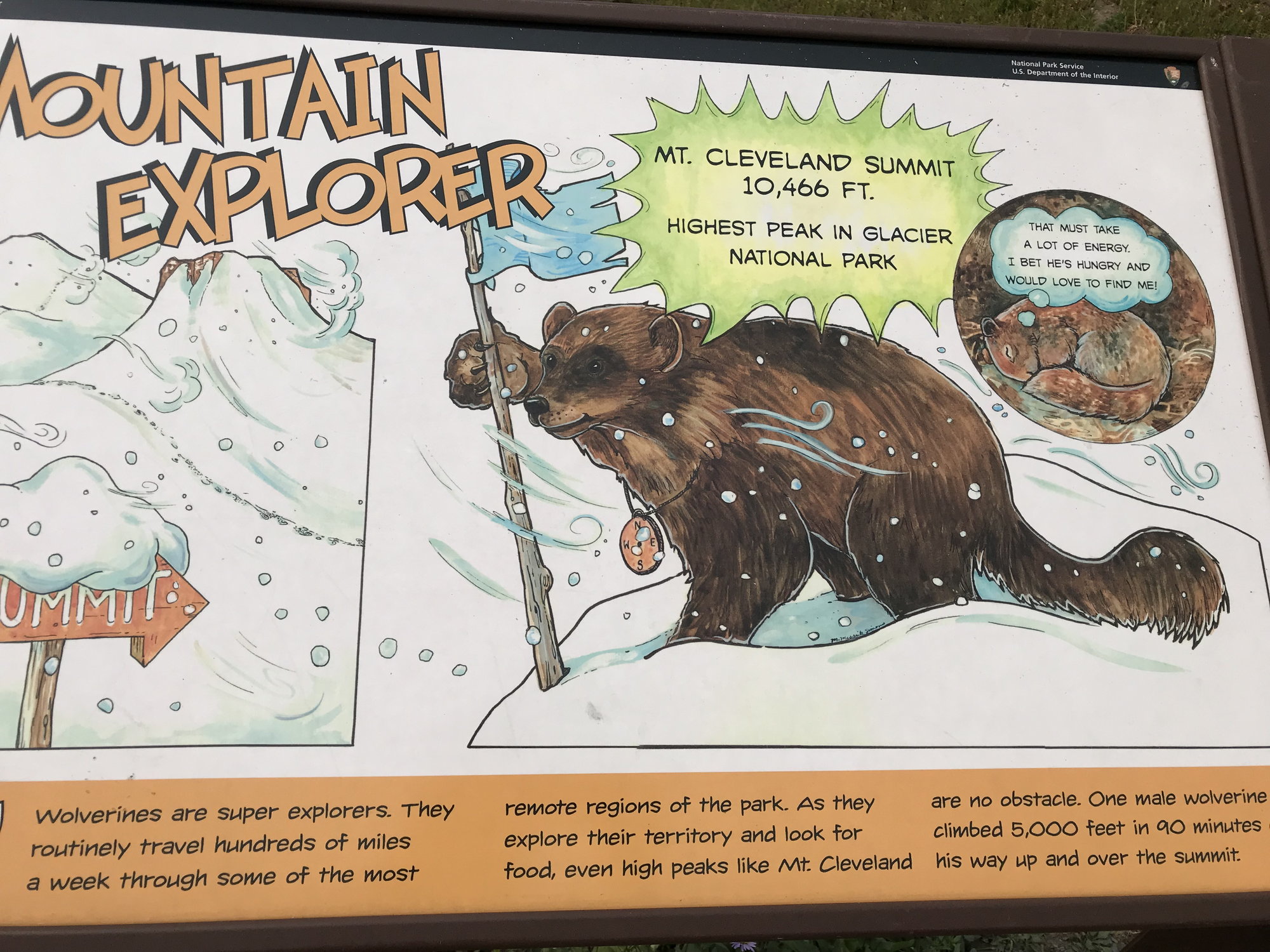

The lowering rays of the late afternoon sun nicely set off the wildflowers as we passed back across the Hanging Gardens at about 4:30 p.m., and we saw several bighorn sheep on the lower slopes of Mount Clement above us. There was also a remarkable marker back outside of the visitor’s center about wolverines, discussing the extensive ranges they cover and their ability to make remarkable time even while scaling Glacier’s daunting peaks (data presumably collected by those tracking collars).

Wolverine marker

And then it was time to commence our 100-mile drive back to Apgar. By this time, St. Mary Lake was largely obscured by smoke as we drove back down the road. We had learned that we could make a quasi-reservation at Serrano’s in East Glacier – just call them and tell them roughly when you expect to get there, and they’ll make sure you get seated when you arrive – and this worked like a charm, notwithstanding the throng waiting outside. It was one of the best Mexican meals I’ve ever had, and the food came in heaping quantities.

Happily, my son (who had also started out driving that morning) agreed to shoulder the driving duties again for the final 60-mile leg back to Apgar. We got in around 9 p.m. While it was still a very good day, the existence of the fire had clearly been more of a problem (except in terms of finding parking at Logan Pass) than it had been the day before.

We also stopped at Silver Stairs Falls (milepost 188.2), which the Moon Guide said “tumbl[es] thousands of feet” (?? Angel Falls, move over?) and is supposed to be pretty dramatic in June and July when the snow runoff is at its peak. But by mid-August, after many 90-degree and a few 100-degree days, the rocky cliff looming above us was merely shaking off drops of water like a dog after a bath.

Silver Stairs Falls, at low water

With these stops, we reached the Two Medicine entrance area at almost the same time we had the day before, and with the same result: no entry. However, I have encountered some suggestions in on-line videos that given the limited parking capacity in Two Medicine, this is capable of happening in Glacier’s peak tourist season even without a fire blocking Going-to-the-Sun Road. Moral: if you want to see Two Medicine, get there early (which is actually pretty good advice for Glacier in general).

We made a pit stop by the Glacier Lake Lodge, then followed our trail of the day before back through Browning. This time, however, we stopped to see the Museum of the Plains Indian, a federal government economic development effort from the 1940's that, while it lacked modern-day museum display razzle-dazzle, we nevertheless found informative and interesting. Its coverage extended beyond the Blackfeet to other plains tribes as well, and was heavy on religion, costume, tools, and hunting techniques and equipment. Photographs were not allowed, however, so I have none to offer.

After the museum, we stopped by the tribal arts and crafts store. The Blackfeet are known for beadwork, so I picked up an elaborate piece depicting a bear silhouetted against the sky that today hangs from one of the shelves in my man cave.

We then continued along our route from the day before back to Highway 89 and on up towards the St. Mary entrance and the eastern end of Going-to-the-Sun Road. The day before, the vistas of the St. Mary Valley had prompted us to pull over repeatedly for photos, but today those views were significantly compromised by the thickening smoke drifting over the Continental Divide from Howe Ridge.

I had assumed we would stop at the NPS Visitor Center at St. Mary and catch the shuttle again, but my family members wanted to go for it and drive, so that’s what we did. As soon as we approached the first parking area, it was clear that the smoke was keeping people away. When we reached the parking area at Logan Pass up at the Continental Divide, we had no problem at all finding space – but it was also evident why this could normally be a very challenging proposition. As you might expect of a parking area located at the top of a mountain pass (with an elevation of 6,646 feet, some 2,200 feet higher than St. Mary, and 3,400 feet above Lake McDonald), there just isn’t that much flat space up there. The Moon Guide said that most days you need to be there before 8:30 to be confident of getting a space. So at least we got that one benefit from the fire.

The parking lot at Logan Pass, late afternoon

We walked through the NPS Visitor Center in the pass and enjoyed its diverse collection of stuffed wild animals. Next, we decided to stretch our legs on the highly popular Hidden Lake Trail, which runs 1.5 miles across the alpine tundra to the Hidden Lake Overlook. This is pretty surely the most heavily-trafficked trail in the park, but it wasn’t bad by this point in the afternoon. It starts off as a boardwalk and initially runs through an area called the Hanging Gardens that is dense with mosses and wildflowers watered by streaming rivulets of snow melt coming down from Mount Clements, which looms above you to the right of the trail. There were subalpine daisies, indian paintbrush, shrubby purple penstemon, and stemless goldenweed.

Stemless Goldenweed

Shrubby Purple Penstemon

Eventually, at the crest of the trail, you enter into a belt of fir trees just above the overlook. Just as we passed a marker for the Continental Divide at mile 1.2, we looked to the right and saw a mother mountain goat and her calf resting comfortably on the ground only about 75 feet away! We paused to take photos, but they were utterly unfazed by our proximity; the mother had a tracking collar around her neck, so presumably she is somewhat accustomed to the human presence. We remembered how back in 2016 we had been thrilled so see four mountain goats moving across a steep slope in Denali, probably at least a full mile away and looking like the tiny white aphids I occasionally see on garden plants. And now, there they were – making us all feel a little silly about our hike to the Goat Lick a few hours before.

Mother mountain goat and calf

More was to come. We reached the overlook and took in the view of Hidden Lake below us – so named, I presume, because you cannot see if from Logan Pass – but today it was further veiled by a soft layer of gray smoke. It was another 1.5 miles down to the lake, making for a 3-mile round trip, and from both a photographic and a breathing standpoint, there was clearly no reason to proceed any farther. When my daughter and I climbed a bluff behind the overlook to take some pictures of the surrounding peaks, which were still raising their summits above the smoke, we encountered a male mountain goat moving through the trees who likewise seemed completely indifferent to us (he, too, was wearing a tracking collar). He ultimately decided to settle down and make himself comfortable next to a fir tree only about 20 feet away from us: “Don’t mind me,” his manner seemed to say. More pictures.

Mountain goat # 2

Then we headed back up the trail towards to Continental Divide – where another, younger male mountain goat, unadorned by a tracking collar this time, came ambling down the trail in our direction. We stopped, and so he detoured off the trail (“I know the drill”) and passed by us through the fir trees along the edge of the trail as he continued on his way. A short distance below us, he started to cross the trail and then paused, looking down it towards the Hidden Lake Overlook. This caused an approaching solo hiker who came into sight a moment later to suddenly startle and pull himself up short. The goat contemplated him for a moment, then almost shrugged – “Seen one hiker, you’ve seen ‘em all” – and ambled on his way. These successive encounters made it very easy to decide which stuffed animal we would get for my grand-niece when we got back to the Visitor’s Center.

Mountain goat # 3

Stuffed animal assortment, Logan Pass Visitor Center