On visiting one of the world's most fascinating borders.

North Korea is a mysterious place and pretty much impossible to visit. The closest that the average North American can get is on a guided tour to the Korean demilitarized zone, or DMZ: the narrow strip of land between North and South Korea. I don’t have a death wish, but I’m definitely curious, so when I decided to go to Seoul, a DMZ tour was at the top of my list of things to do.

There are several different kinds of tours available, but only one actually gets you to the Joint Security Area (JSA) inside the DMZ, where visitors are able to physically step foot on the North Korean side of the border. The problem is that these tours book up months in advance, and even if you do get a place, it can be called off at the last minute if there’s a political affair happening. For the best chance at getting into the DMZ, sign up as early as possible. If your travel is relatively last minute, though and the JSA tours are full, be assured that there are a variety of other tours that still provide fascinating insights (plus it’s worth asking about last-minute cancellations that might open up a spot for you). That’s how I got on a JSA tour although I had originally only signed up for a “One Korea” tour.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Look for a tour that takes you to one of the several infiltration tunnels that were dug by the North Koreans–presumably to enable an attack on South Korea–and to the learn the most about North Korea, opt for a tour with a guide who has actually defected from North Korea, so you can ask questions about his or her personal experiences.

Most of these tours take the better part of a full day and usually include lunch. If you’re going to the JSA, there is a rather strict dress code to adhere to: no shorts or T-shirts (only collared shirts) and no tank tops or sleeveless skirts; skirts and dresses need to knee-length; no jeans with holes; no stretch pants or tights and no exercise clothes; no sandals or flip-flops. If you aren’t dressed appropriately or don’t have your passport, you won’t be allowed on the tour.

Park Shin Sook, the North Korean defector who spent the day with my tour, is a petite and vivacious middle-aged woman with short hair who was more than eager to talk about her life in North Korea and why she had left, and I had plenty of questions. As we set off on the bus, Park explained that she had left her home in North Korea in January of 2011 with her daughter and her mother. Someone asked, why hadn’t her husband come with her, and had he known she was leaving?

“I couldn’t tell him, because I was afraid he would report me,” Park explained. She had joked about it to him, but he had only ever got angry at the idea of people leaving, so she knew she couldn’t tell him. She’s had no contact with him and has no idea what happened to him since.

She told us that in the 1970s, her family had lived a good life–even better than people in South Korea. She had been an architect, and her husband also had a good job, and they were quite wealthy, but then the government had begun to focus on nuclear armament and salaries disappeared. She had saved a lot of money to send her daughter to college, but with the dollar reforms, it was only enough to buy rice and soon, all their savings were gone. That’s when she knew that if she wanted her 17-year-old daughter to have an education, she had to leave.

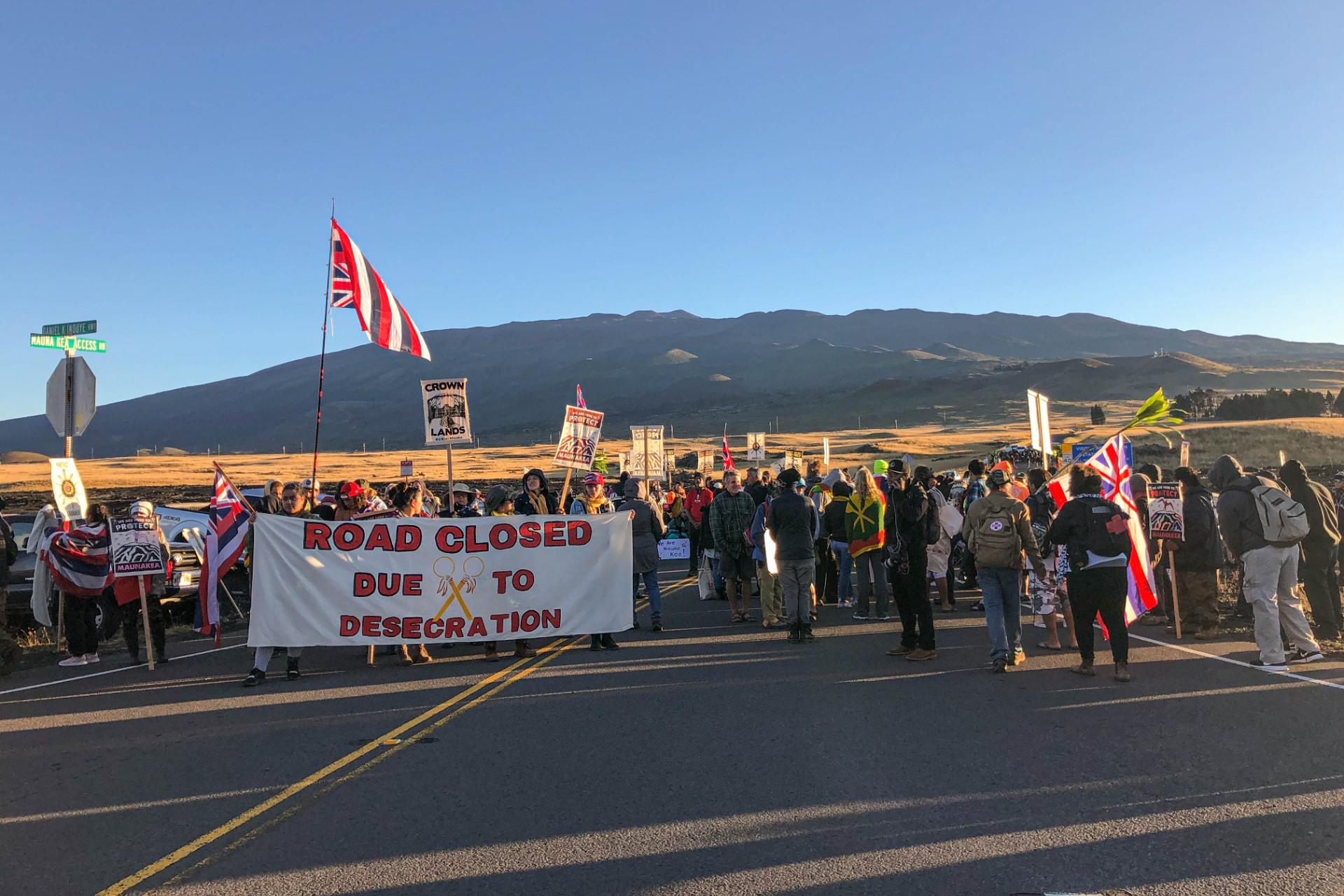

The first stop on the tour was “Imjingang Resort,” which, although it has a pretty, landscaped park and a few restaurants, isn’t a “resort” at all. What visitors come to see is the Freedom Bridge that crosses the Imjin River between North and South Korea, where prisoners were repatriated at the end of the Korean War in 1953–of course it’s completely blocked off and no one can cross, though there’s an observation point where tourists can pay for a closer glimpse of North Korea. There’s also a barbed-wire border fence hung with colorful memorial banners and streamers with messages left by South Koreans to their families in North Korea, who they have not been able to see or contact.

When we were back on the bus, I asked Park how much she had known about the outside world before she left North Korea. She and her husband had lived close to the border with China, she explained, and after she stopped being an architect, she had worked in a flea market to make money. At the market, there were many Chinese smugglers who sold foreign goods and brought information and news about the world. This was also where she had found the smugglers to get her family out.

The escape involved six months of arduous travel through China, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand to get to South Korea, where Park’s sister lived. If defectors are caught in China, they are usually sent back to North Korea. When they had arrived in South Korea, life was difficult. South Koreans spoke a different dialect than she had known, with a lot of English influences, and she’d had to undergo two months of government investigation to make sure she wasn’t a spy. After that, though, the South Korean government gave Park and her family a lot of support, including housing. With the difference in technologies from North to South Korea, Park could no longer be an architect, but the South Korean government paid for her to go to school.

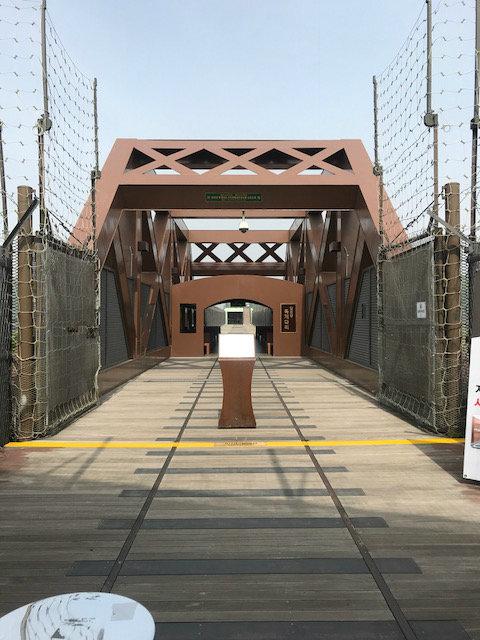

Back on our tour, we arrived at Dorasan Station railway station. It’s clean and shiny and newly restored, all set to begin commuter service between North and South Korea–just as soon as the two Koreas are reunified. You can buy a train ticket and stand on the platform, but you’ll be waiting for a while.

From there it was a short drive to the Third Infiltration Area, one of several tunnels that had been dug under the DMZ by the North Koreans to invade South Korea, that had been discovered in the 1970s. I had worried this was going to be Disney-kind of experience, but I shouldn’t have been concerned: there was no gloss here—unless you count the condensation dripping on the walls. We put on hard hats and slowly descended on an open monorail through rough-hewn rock. At the bottom of the sloping tunnel, we walked about 10 minutes more, ducking at some parts and watching out for jagged rocks, to where the tunnel had been sealed off from North Korean access. I could see a small window in the concrete and iron to what looked like a small tree on the other side. Back above ground, a short movie explained how the several tunnels were discovered, and how they could have fit battalions of North Koreans and their weapons for a surprise attack on the south.

Then we went to the Dora Observatory, where telescopes are set up to see across the DMZ into North Korea. Unfortunately, it was quite foggy that day and we couldn’t make out much of what we were told was a “Propaganda Village” built in the 1950s by the North Koreans emulate an idyllic village of several hundred people wired with electricity. In reality, it is believed to be a shell of a town with deserted streets and lights in the buildings that turn on and off at fixed times.

As the rest of the tour group wandered around, I asked Park about her daughter. She told me that she had gone to school in South Korea and studied Chinese and was now living in China. Park wanted to take her daughter to Canada, though, so that they could learn English. I laughed and told her that I was from Canada, but that it was too cold there, knowing perfectly well that the weather in North Korea is the same or worse. She laughed, too, and said that the weather in Canada is very much like in her hometown. We both pretended to shiver in the cold.

Then we got back on the bus for what was meant to be the highlight of the tour, stepping on North Korean ground. I stared out the window into the trees as we drove alongside the DMZ. Park explained that since no one had entered the DMZ for more than 60 years now, the dense growth had basically become a wonderful natural habitat where birds, animals, and flowers flourished. The bus driver drove very carefully, though; you don’t want to accidentally drive off the road amid the road signs warning about landmines. Along with the wilderness is Daeseong-dong, a village located inside the DMZ where the farmers have been granted large plots of land to grow rice–the limited quantities that can be grown in the small but fertile area make “DMZ rice” a precious commodity–but the residents also have to deal with living in a military zone, the attendant curfews, and limited mobility.

As we approached JSA, the area controlled by both North and South Korea, Park explained the dress code rules that we’d been given. The reason that no ripped jeans or very casual clothes are allowed is because in the past, North Korea has taken such photographs and used them as propaganda, insinuating that the people who lived outside North Korea are so poor that they can’t afford nice clothes. Visitors are not allowed to wear flip-flops or slippers just in case of any incident that might require visitors to run (!). And, she continued, no one is allowed to drink alcohol at lunchtime, again in case of an “incident,” and to make sure no one would get disoriented and run in the wrong direction.

“Welcome to paradise,” Park intoned, deadpan, and we laughed (maybe a bit nervously).

The bus drove into the JSA zone and two UN military personnel came onboard to check passports, then we tramped off the bus to a conference hall where we listened to a short lecture and signed a piece of paper stating that we were aware we were entering “a hostile area [with] the possibility of injury or death as a result of enemy action.”

Then we got back on the bus and drove to the set of blue buildings that straddle the demarcation line that separates North and South Korea. The soldiers of the Republic of Korea stand at attention, wearing mirrored sunglasses so that the North Koreans can’t make eye contact. And they stand partly to the side of the buildings—just in case shooting breaks out, as it has in the past.

And then one of the UN soldiers got back on the bus and said that at the last minute, we’d been denied access to the grounds because of “renovations,” but we could take pictures from the bus. We spent a few minutes snapping photos out the windows, and then we drove back to the gate where our passports were all checked again—to make sure everyone was there and no one had tried to defect to North Korea.

And then we drove out of the JSA area and made the inevitable last stop–the gift shop, for drinks, snacks, key chains, postcards, t-shirts–before heading back to Seoul. If I’d had room in my bag, maybe I would’ve bought the 20kg bag of DMZ rice or a North Korean soldier bobblehead (around $10 USD).

Before we left, I thanked Park for being so kind for telling us her story. We took selfies together, of course, because we live in the modern world but I won’t be sharing those anywhere–there’s still a real concern that she or her husband, still living in North Korea, could suffer for it.

To book a tour of the DMZ with a North Korean defector go to www.panmunjomtour.com or http://onekoreatour.com