The Mekong River, for those of a certain generation, flows with melancholy. The mental images it conjures are as clear today as when they were broadcast over Walter Cronkite’s shoulder on the Evening News 50 years ago.

But I was curious about Vietnam and Cambodia. I had heard from other travelers that they were fascinating and welcoming destinations. So, I decided to take a cruise on the Mekong. The itinerary would take us from the Mekong Delta in southern Vietnam to Kampong Cham, Cambodia, some 328 serpentine miles north. As I suspected, the trip would prove to be an eye-opener.

Day One: Setting Sail

My initial glimpse of the Scenic Spirit occurred on the dock at My Tho, Vietnam, where I was initially put off by the ship’s elegance, its vast picture windows, its bright shiny whiteness. Launched in 2016, the Scenic Spirit is arguably the most luxurious ship on the Mekong. The swimming pool—a rarity on river cruises—was deep and long enough to swim laps. Considering that the ship has five decks, the central elevator (another rarity in river cruising) was a blessing. All the rooms are suites with balconies. The windows in my quarters went from floor-to-ceiling in both the bedroom and sitting room. The dressing room was far too large for a single traveler, and probably for two. Oh, and did I forget to mention the personal butler? Any reservations I might have harbored about a first-class ship in a third-world country dissipated as we sailed at sunset.

Recommended Fodor’s Video

Day Two: Cai Be – Tan Chau, Vietna

In Vietnamese waters, the Scenic Spirit was obliged by regulation to anchor in mid-river, so guests were tendered by sampans to their shore excursions. That’s how I arrived in Cai Be, our first stop, a busy village dominated by the graceful steeple of its Catholic church. As I roamed the streets, I saw girls hand-rolling candy, men making popped-rice snacks, factory workers separating coconut meat from the husks. The industriousness of the people was impressive.

I met a man in Cai Be selling snake wine from two five-gallon glass jars. The wine-seller, a guy with a mustache and a leer, pulled a dead cobra out of the jar and held it in front of the faces of aghast tourists, challenging them to drink. Always ready to test myself (and usually to my regret), I asked for some. The slinky sommelier smiled, waggled the cobra in my face, and then decanted a thimble-size serving. Glass in hand, I held my breath and poured the liquid down my throat. Moments passed. When at last I could breathe again, I realized the wine tasted a little like Japanese sake. “They believe it improves men’s, er … ability,” said my guide. “Men drink, women happy.”

That afternoon we anchored just offshore of Sa Dec, a town farther upriver, known as the setting for the romantic novel (and later film) The Lover [L’Amant], written by Marguerite Duras. Many of the passengers were eager to see the 19th–century house where much of that tale of forbidden love takes place. But I was far more interested in visiting the lively street market. The sounds of the market were rife with songs that resembled the schoolyard taunt, “Nya nya nya-nya nya,” but in fact were sellers announcing their wares—prawns, tiny bananas, tripe, catfish, mice (meant to be marinated and grilled), snakehead fish, frogs, and live free-range chickens. (The chickens sell for $4 a kilo; for an additional 50 cents they’ll dispatch your chicken and pluck it for you.)

In was in the Sa Dec market that I met a woman selling betel nuts, which, when chewed, are a mild stimulant that leaves users’ teeth red. I saw no redness on her teeth and asked if she liked to chew her product. She made a face of disgust, then giggled. She never chews them, she said; she doesn’t like the taste. She seemed quite amused at the thought of selling a product she didn’t even like. Yet she earns about $10 a day selling the nuts to her customers, she said. Considering the average Vietnamese worker earns $150 a month, no wonder she smiled so much.

Day Three: Tan Chau, Vietnam – Cambodian Frontier

Some days were spent mostly on the river, and this was one of them. But first I opted for an excursion to a farming village on Evergreen Island near the town of Tan Chau. The village, on first look, struck me as impoverished, but then I noticed that corrugated metal roofs outnumbered those of palm fronds. Though the houses, raised on pilings, were rickety, they were neat and organized. Next to the entrance of each home was a large ceramic jar of water for entrants to wash their feet before walking inside. Traditional music wafted out a window, and our guide, Tuan, gently swayed to the tune.

We passed a chili farm with hot but not-too-hot chilies (I know because I plucked and tasted one). The chilies are sold mainly to China, where they are in high demand. The farmers earn between $4,000 and $5,000 a year by growing chilies for the Chinese market, Tuan said. Besides chilies, the farmers here grow bananas and mangoes. “They’re a very happy people,” said Tuan. “Life is getting better since the government allowed the market economy. The life is improving.”

Boys and girls followed us as we walked along the dirt lanes. When we pointed our iPhones at them, they laughed, punched one another in the arms, mugged for the cameras, and waved as they rode away on their bikes—just like kids anywhere in the world.

Day Four: Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Almost immediately after crossing into Cambodia, one could notice a difference in the surroundings. The fishing villages seemed to be made of poorer materials. Fewer cars and trucks plied the riverside roads. Gone were the cement company dredgers scouring the river bottom for sand, as in Vietnam. Palm-frond roofs outnumbered those of clay tile and corrugated steel. Unlike Vietnam, Cambodia seemed like a land stuck in the past.

Those who recall the Vietnam War will likely remember Cambodia’s most hellish period, the brutal Khmer Rouge regime of 1975-79. As a result, shore excursions in Cambodia assumed a poignancy.

While some passengers chose to spend that first day in Cambodia touring Phnom Penh’s French-colonial architecture or taking a cooking class, many of us decided to see a more disturbing part of the country’s heritage. Our first stop, just a few miles outside the capital, was the notorious Killing Fields. There and elsewhere, some 2 million everyday citizens were murdered by the Khmer Rouge, who sought out so-called intellectuals—often anyone with an education, or even who just wore glasses—for fear that they opposed the regime.

Returning to the city, we paid a visit to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, a Khmer Rouge prison in a former high school they renamed S-21. I was surprised at the crowds waiting in line to buy tickets for such an unlikely attraction. We walked among tiny jerry-rigged cells where prisoners had been grilled and beaten. Chains still dangled from bare metal bedsteads where torture victims were once shackled. Barbed wire still screened the jail’s upper floors, placed there to prevent despondent prisoners from taking suicide leaps. Bolts on the cell floors showed how the victims were fettered in place, awaiting their fate.

One whose fate was not sealed at S-21 is 86-year-old Chum Mey. I met him that morning in the yard of the prison where he was once incarcerated. “I was tortured and my wife was killed by the Khmer Rouge,” Chum Mey told me through an interpreter. He survived “re-education” and was sent to work as a laborer. Thirty years later, he wrote a book about his experience. Now he comes to the former prison every day to sell copies of his book and to meet the tourists. “I’m very happy to see all the people coming here,” he said. “I hope you will go back home and share my story with your friends.”

Day Five: Phnom Penh – Koh Chen, Cambodia

The next morning I joined a tour of the Royal Palace and National Museum. Their elaborate traditional architecture, lush landscaping, and peaceful settings helped take the edge off the previous day’s unsettling excursion.

At noon, we pulled away from the dock at Phnom Penh and made our way north to Koh Chen, a silversmith village where some 150 families operate out of homemade factories, often little more than a covered patio attached to a house. My fellow passengers were intensely curious about the trade, asking for demonstrations of the silver-plating process and browsing the shelves for souvenir bracelets, necklaces, and rings.

The streets of Koh Chen, like in so many Cambodian villages, are hard-packed dirt. As we followed one of those roads, we passed a group of boys playing soccer on the grounds of a multi-colored temple. Some in my group didn’t realize they were interrupting the boys’ game to take pictures of the temple, but the kids just smiled and waved when any of us made eye contact. The boys seemed to take it in stride, but I regret that I didn’t know the Khmer language for, “Sorry we messed up your game, guys!”

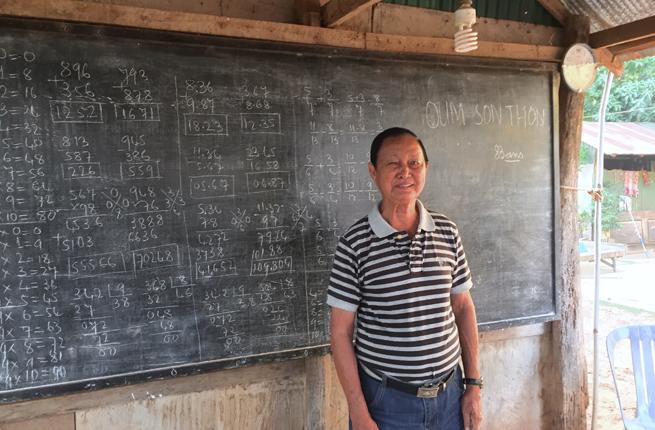

Just around the corner from the temple, we met Oum Son Thon, 83, a former teacher who survived the Khmer Rouge by impersonating a laborer. He now has the finest house in the village, thanks to his successful offspring. Next to his home is an open-air classroom where he teaches math to the local kids. He takes much more pride in his 30 students than in his handsome villa.

Day Six: Koh Chen – Kampong Cham, Cambodia

The average age of the passengers on the Scenic Spirit was somewhere in their sixties, but that didn’t stop most of them from rising early for an unusual trip: a 20-minute ox-cart journey on washboard roads to a small temple. The phrase “bone jarring” comes to mind. All the travelers were good sports about the rough ride, but clearly grateful to then board modern motor coaches for our main destination, Oudong Temple.

Sometimes it’s useful to research everything in advance; other times, it’s more rewarding to embrace the mystery. That’s what happened to me in the Oudong pagoda, where we sat on the floor in the shadow of a massive Buddha statue while two monks chanted for 15 minutes. “We invite the gods to remove sin and return prosperity to the earth,” one of them said, through a translator. Then, unexpectedly, they began to throw lotus buds at us. They were pretty hard, too—hard enough to make me close my eyes and duck my chin. And then, like my fellow passengers, I laughed quietly, marveling at the strangeness of it all.

Day Seven: Wat Hanchey – Kampong Cham, Cambodia

I met a 13-year-old novice monk on my last full day on the Mekong. The place was called Wat Hanchey, some of whose temples are older than their more famous cousins at Angkor Wat. The boy’s family name was Chea; his given name was Chek, which means banana. “My family comes to visit me once a month,” he said, with a shy smile. His favorite subject in class was literature. When asked about his future, he said he didn’t know how long he would remain at the temple, but he likely would be a novice until age 15, at which time he could go on to high school and, possibly, university. His ultimate goal? “I would like to be a doctor,” he said.

Day Eight: Kampong Cham – Siem Reap, Cambodia

Most river cruises on the lower Mekong end near Kampong Cham, and passengers are taken by motor coach from there to Siem Reap and its international airport. Some guests stay on to visit the temple complex at Angkor Wat, while others fly directly home. The four-hour coach ride, which at one point passed over a centuries-old stone bridge, is a perfect time to reflect on the past week’s experiences. The visits ashore had their stark moments, to be sure. But to cruise the Mekong, whether on the Scenic Spirit or any of the competitive ships, is mostly an upbeat, often heartwarming journey through one of the most remote, colorful, enchanting corners of the world, full of music, full of smiles, full of mysteries unraveling before you.

And do I worry that the luxurious, cosseting confines of the Scenic Spirit were at odds with what I was seeing? It’s a specious premise. People were talking across borders, contributing to the local economies, making contacts, friends even, at a time when the world is roiled by fear. Our little river haven may not have been indicative of society at large, but it had a hell of a lot going for it.